NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Former NFL star Joe Theismann will enter the 2025 American Century Championship as one of the veterans in the celebrity golf tournament.

Though the former Washington Redskins quarterback has only won the Korbel Hole-In-One Contest at Edgewood Tahe Golf Club, he told Fox News Digital he is as excited as ever to be a part of the tournament once again this year.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE SPORTS COVERAGE ON FOXNEWS.COM

Joe Theismann, right, signs autographs at Edgewood Tahoe Golf Course on July 10, 2019 in Stateline, Nevada. (Jonathan Devich/Getty Images)

“I’ve played in 35 of 36 (tournaments),” he said. “I certainly circle those days. The American Century Championship has been unbelievable as far as competition goes, the people you get a chance to be around.”

Theismann highlighted the charitable component of the American Century Championship as well. Millions of dollars are raised during the festivities to benefit the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and the Eat. Learn. Play. Foundation.

“American Century puts on a great week for their customers and for all of us. They have karaoke nights, and they have great dinners where you get a chance to interact and see people you haven’t really seen,” Theismann said. “My wife and I really look forward to it. You learn so much.”

Former Notre Dame quarterback Joe Theismann waves to the crowd during an NCAA college football game between Notre Dame and Stanford at Notre Dame Stadium on Saturday, Oct. 12, 2024 in South Bend, Indiana. (MICHAEL CLUBB/SOUTH BEND TRIBUNE / USA TODAY NETWORK via Imagn Images)

He said he got to talk to Buffalo Bills star Josh Allen about his 2023 season last year and delighted in speaking with actor Miles Teller.

“’Top Gun: Maverick’ is one of my favorite movies in the world. So, I had a chance to see him last year. I was like a little kid,” he said with a laugh. “He was on the range hitting balls. I didn’t want to bother him, but I wanted to say hello.”

Miles Teller is seen on May 29, 2025 in New York City. (MediaPunch/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images)

WWE STAR THE MIZ VOWS TO BEAT NBA GREAT CHARLES BARKLEY AT THIS YEAR’S AMERICAN CENTURY

Theismann was not embarrassed to admit he was a bit of a “fanboy” when it came to Teller.

“I’m not embarrassed,” he told Fox News Digital. “There are certain people that I’ve met. I’ve been blessed to meet people, whether they’re heads of state, heads of countries, many presidents, CEOs, some of the most incredible people in the world I’ve had a chance to meet and just to be able to continue to watch people and see them and really get to know what they’re like, what makes them tick. That’s what I enjoy – getting to know the person.”

Theismann was tied with Joe Flacco and Jason Scheff last year and tied for 46th with A.J. Hawk and Seth Curry in 2023.

This year, he is hoping for some improvement, though he admitted his game is getting shorter and shorter as the years go on.

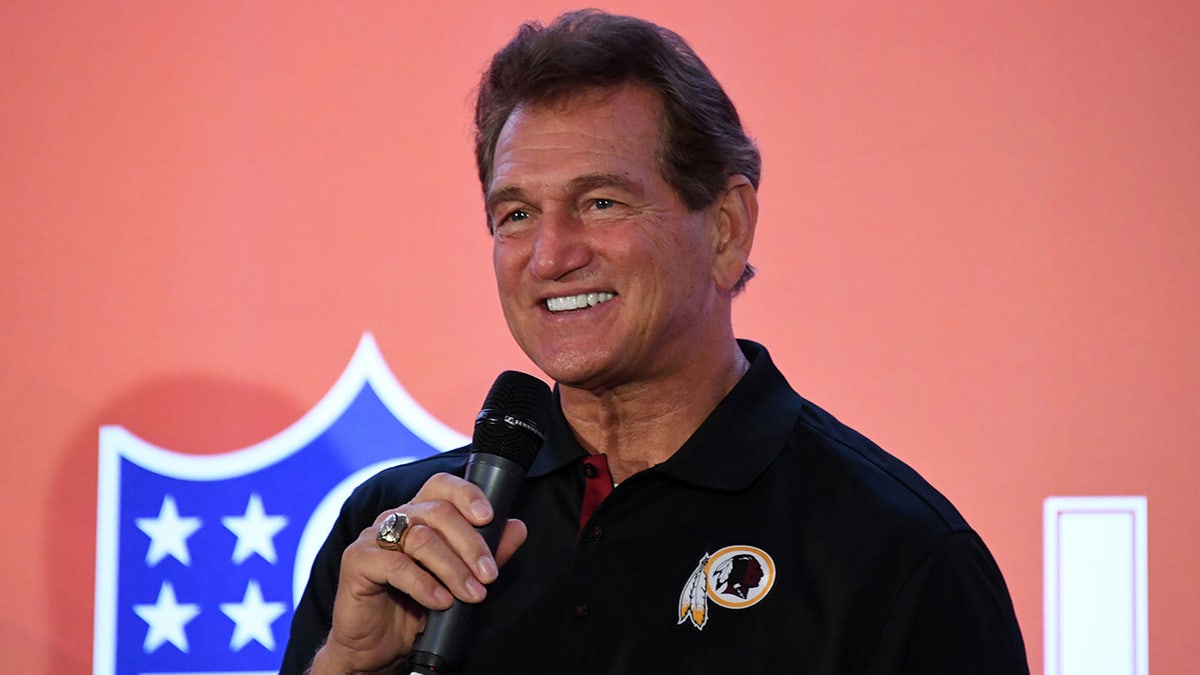

Washington Redskins former quarterback Joe Theismann during the NFL International Series Fan Rally at the Victoria House in London on Oct. 29, 2016. (Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports)

Theismann said fans can also get in on the action with a fantasy game that was developed for the tournament. He said fans can begin to register next week with the winner getting two tickets to next year’s tournament and a $10,000 check to the charity of their choice.

The event is a 54-hole Stableford format in which golfers earn points for each hole based on the score to par. The golfer who achieves the most points wins.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The tournament kicks off July 9 and runs through July 13.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Ryan Gaydos is a senior editor for Fox News Digital.

Comments are closed.