SINGAPORE: Every month, corporate employee Ms Xianggui from China’s Jiangsu province generously sets aside a fifth of her 10,000 yuan salary (US$1,371) towards her ageing parents’ retirement fund.

Like other single adults living in China without siblings, the 29-year-old, who asked to have her full name kept private, bears the weight of being the sole financial provider for her parents, both in their 50s.

She began setting aside more money after learning that her parents would only receive around 300 yuan each month, post-retirement and now hopes to save at least 200,000 yuan in the next 10 years.

Hers is a predicament faced by many “single-child families” in China, which comes as a result of the one-child policy and has riddled the country with demographic problems.

“Many families in my village only had one child in response to national policies,” she told CNA, adding that she hopes the national scheme could soon be improved to increase payouts and reduce financial burdens faced by adult only-children.

China’s pension system has been facing immense pressure in coping with a rapidly ageing population and declining birth rates, which has resulted in a declining pool of working-age people funding the system and more retirees looking to receive payments.

While the government’s move to raise the retirement age from January 2025 is a step in the right direction, experts say that it is still not enough and more clearly needs to be done to support the national pension scheme.

There is little money leftover for Ms Xianggui after deducting living expenses, retirement savings and allowances for her parents so she has had to postpone personal plans like buying her own house and getting married.

“My parents’ monthly pensions are far too low, which deeply concerns me,” she said, adding: “As an only child, the entire burden falls on me.”

A FRAMEWORK UNDER PRESSURE

China ranked 31st in the world for pension systems, out of 48 countries, according to the 2024 Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index, scoring 56.5 with an overall C grade – a marginally better score than the 55.3 it received the previous year.

But it received a dismal D for sustainability, highlighting concerns about the system’s ability to provide sufficient retirement income and maintain long-term financial viability.

In comparison, Nordic countries like Sweden, Iceland and Denmark, known for their robust and well-balanced pension schemes, scored 74.3, 83.4 and 81.6 respectively, while Singapore’s Central Provident Fund system came in 5th with a score of 78.7.

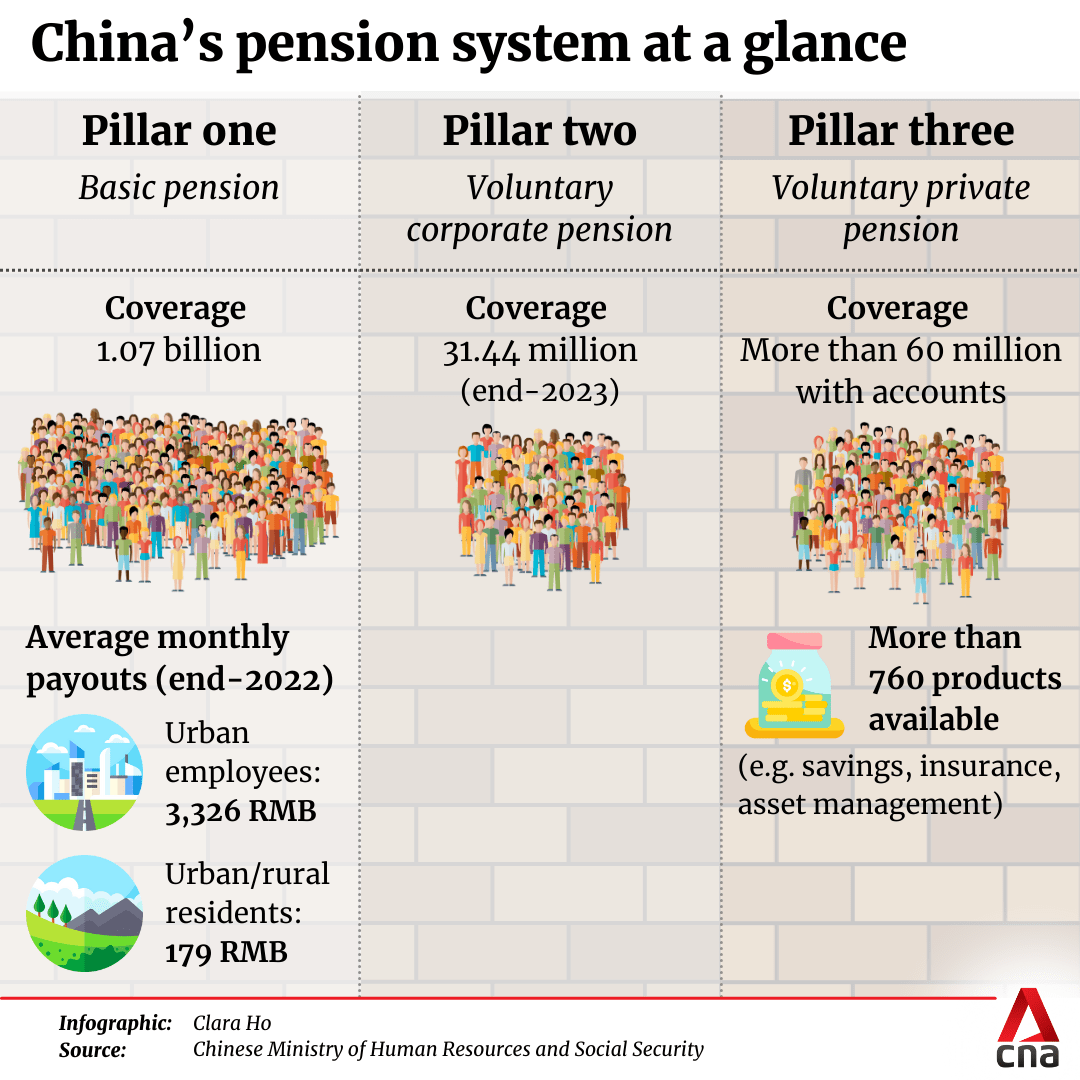

According to official statistics, China’s pension system covers more than 1.07 billion people across the country and is made up of three pillars.

The basic pension system is led by the state, covering urban employees as well as urban residents and rural residents.

Then, there’s the voluntary employee pension plan from employers which has relatively limited reach.

Finally, a private voluntary scheme that was launched in 2022 and continues to see low participation rates as of June 2024, with just over 60 million people opening new accounts.

But despite the broad coverage, the difference in payouts among working classes remains huge, analysts said, noting that only around 503 million people, half of the more than 1.07 billion people, were considered eligible for generous urban pension plans.

Average monthly payouts for urban workers and business owners amounted to around 3,326 yuan as compared to only 179 yuan which workers and residents in rural areas received.

Ms Zongyuan Zoe Liu, a Maurice R Greenberg senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), told CNA that the sufficiency of payouts “still needed to be improved”.

“The coverage ratio is impressive but the amount (that) people can withdraw is small,” she said.

Those in prestigious fields, like former civil servants, doctors and schoolteachers, received the most generous benefits.

On the other hand, migrant workers and others from rural areas were often excluded from higher-paying employment-based pension schemes, even if they had lived and worked in other cities for a long time.

“Peasants and rural-to-urban migrants are the most disadvantaged in the pension system as most of them are enrolled in the resident-based track with the lowest benefit rate,” said Dr Huang Xian, an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Rutgers University.

“Individuals with rural roots are always placed at the bottom of the hierarchy for benefit distribution as they are the most distant from the regime in socio-political status.”

PENSION POT RUNNING DRY?

Besides inequality and insufficient support particularly for migrant and rural workers, the entire pension system is facing a major challenge because the pot is believed to be running dry soon.

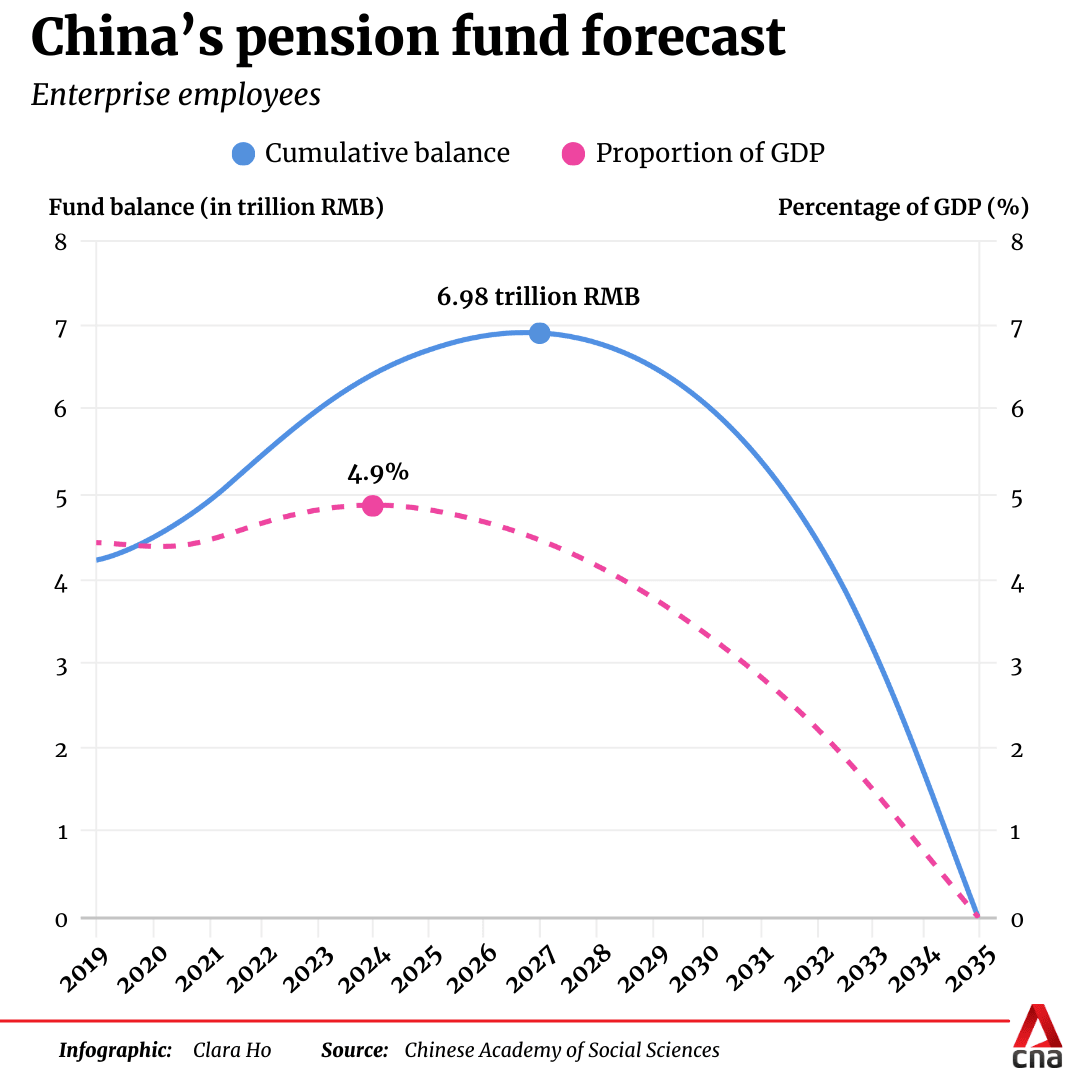

In 2019, the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) warned about a potential depletion of pension funds for urban employees by 2035.

That estimate was however made before the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, so analysts say the bomb may be ticking even faster.

“A lot of the COVID-19 era pension or insurance health care deficits created negative shocks,” said Ms Liu, adding that there was also a chance the national social security fund could be depleted even before 2035.

According to a 2021 government report, China’s social insurance funds recorded the first annual deficit in 2020, after authorities cut corporate contributions to help companies offset the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic. The funds’ combined revenues fell 13.3 per cent in 2020 while expenditures rose 5.5 per cent.

The shift toward gig and informal workers also raises challenges for pension revenue collection, experts said.

“The ability to collect revenue for social insurance is becoming very difficult because social insurance assumes that most of your workforce is formally employed and generally long-term employed under legal, contractual arrangements,” said Mr Mark W Frazier, a politics professor at The New School in New York City.

Public pension expenditure in China accounted for about 5.4 per cent of its total GDP in 2023, an increase from 5.2 per cent in 2022 and 2021, according to data from Statista.

Analysts say this figure, while seemingly moderate compared to advanced economies, is substantial for a developing economy like China.

“The sustainability of that level of collection and payment depends on the future of the Chinese economy,” said Mr Frazier.

“You can always lower the 5.4 per cent expenditure figure if you have a larger economy, but the absolute number of pension expenditures will keep increasing year by year.”

Further faltering of the pension system also risks eroding public trust in the government’s ability to meet its obligations, analysts said, potentially destabilising societal equilibrium.

China’s rapidly ageing population has been affecting the pension system’s sustainability – with more elderly citizens claiming retirement benefits and less working adults contributing to the pension fund.

The population aged 60 years and above reached 297 million in 2023, accounting for more than 20 percent of the total population. This percentage is projected to increase to an astounding high of over 52 per cent by 2100 – meaning more than half the population will be elderly.

The labour force has also been shrinking as the country’s declining fertility rate is now among the lowest in the world, at 1.1 children per woman.

The imbalance has directly affected the country’s dependency ratio, the number of workers supporting each retiree, which is projected to fall from the current 2.95 to just 0.69 in less than 80 years, based on UN population projections, according to Mr Dudley L Poston Jr, a sociology professor at Texas A&M University.

“As a result, financial risk and pressure are overwhelming,” said Dr Huang.

In the meantime, pressure still remains on only children to shoulder the financial burden of their parents’ retirement. “The idea that a child is supposed to take care of the elderly, is a classic family value – not just China in particular but in a lot of (other) Asian countries,” said Ms Liu.

“THE ENTIRE BURDEN FALLS ON ME”

‘Yang er fang lao’, a common Chinese saying, refers to the practice of bearing and raising children to look after you in your old age.

But with the one-child policy implemented between 1980 and 2015, and the current low fertility rate, a whole generation of single-child families is bearing the weight of financially supporting ageing parents on their own.

Ms Xianggui worries about her ability to support her parents long-term and has been conducting her own research on online platforms like Xiaohongshu about increasing pension contributions.

She believes that it is “still possible” to increase her pension contributions to the maximum tier of 4,000 yuan annually.

“Under this new plan (that I came up with), my father would contribute 8,000 yuan annually, and my mother 4,000 yuan into their individual pension accounts. Together, this could raise their combined pensions to over 1,000 yuan per month,” she said.

While it’s a modest amount, she thinks the adjustment is “better than nothing” and “within” her financial capacity.

The youngest of three children, Dove Long, an unmarried 41-year-old living in the city of Changsha, gives both her retired parents a fixed monthly allowance and even goes the extra mile to buy them supplementary private health insurance to “mitigate financial stress in case of major illnesses”.

But despite earning a comparatively higher than average income of around 20,000 yuan (US$2743) per month, Ms Long said she still worries about her own retirement.

For her, long-term financial security remains elusive. “Society generally expects children to take on the primary responsibility for their parents’ retirement,” she told CNA.

“With the rising standard of living, I hope to have enough funds to enjoy a rich cultural and recreational life after retirement, such as frequent travel and participating in various interest classes,” she said.

“My employer contributes to my pension insurance as required… but relying solely on social security pensions may not fully meet my future aspirations for a quality retirement,” she added.

“Under the current system, the estimated pension (I get) might only cover basic living expenses, which falls short of fulfilling all my needs.”

Life expectancy in China has risen to 78 years as of 2021, from about 44 years in 1960, and is projected to exceed 80 years by 2050.

And longer life expectancies will mean more financial strain like the increasing costs of elder support and care. “As people grow older, it’s natural to expect that they might need more medical (help) so expenses will increase,” said Ms Liu. “That added cost will be another financial burden to the family.”

Young adults also grapple with other ongoing financial burdens like stagnant wages and high living costs.

Competition in the job market remains stiff and pressures are high, Ms Liu added.

“The cost of childcare is (also) high,” she said. “This basically means (people) have to spend if they decide to have (a) child, so it’s a lot of expenditure. But the wage growth has stagnated.”

SPEND OR SAVE?

The financial realities have impacted many major life decisions for Ms Xianggui, who shared that she had been planning to buy a house with her fiancé in Hefei, one of China’s fastest growing cities famed for its blend of historical heritage and sci-tech innovations.

The situation has been stressful, she said, adding that the couple has had to postpone their wedding in order to support her family.

“My fiancé’s family is contributing the majority of (our) down payment while I can only provide 200,000 yuan as my parents are unable to support me financially,” she said. “He wants to work for a few more years to save up.”

Rutgers University’s Dr Huang noted that citizens born under China’s one-child policy grew up in a relatively open and liberal era, different from their parents and have “a different approach to navigating challenges”.

“They have better education and more exposure to new media in general, hold less trust in the government or lower expectations for the government’s social welfare responsibility,” she said, adding that they might seek alternative financial services instead of relying solely on state support.

“However, they face similar challenges in balancing elder care and personal financial priorities compared to the older generations.”

The unreliability of the pension safety net means most people “have no choice but to live on personal and family savings and assets after retirement”, said Dr Huang.

“Older people… want to save, to prepare for either retirement or emergencies,” said Ms Liu. “This propensity to save discourages people from consuming, and the lack of household consumption is a very big problem dragging the Chinese economy now.”

She noted that a failure to stabilise China’s pension system could stifle domestic consumption, with global repercussions.

“If families realise they have better healthcare or broadly speaking, better social security, then Chinese families or consumers are willing to spend, rather than just save for the future,” she said.

“The increase in consumption is also going to stimulate the economy.”

NAVIGATING THE ROAD AHEAD

China’s pension system remains at a crossroad and in September 2024, the government announced incremental reforms to raise the retirement age, aiming to ease financial pressures on the pension system.

The move was long overdue, given that China’s retirement age – 60 for men, 55 for women in white-collar jobs, and 50 for women in blue-collar jobs – had not changed since the 1950s, analysts said.

“Extending the retirement age will allow the pension funds to last for some additional years,” said Mr Poston.

However, he cautions that it is not a silver bullet. “This will not be a permanent fix. It will only partly address the extremely serious demographic problems now facing China.”

Mr Frazier, who also authored a book titled “Socialist Insecurity: Pensions and the Politics of Uneven Development in China”, noted limitations of this measure and said long-term effects would not be felt until 2040 or 2050.

“The costs of pensions are never placed directly on people in the current moment, but they are postponed decades into the future,” he said.

The Chinese government has in recent years also sought to diversify the pension system with the introduction of private retirement savings schemes in November 2022.

The introduction of individual retirement accounts (IRA) is a key component of this effort. These accounts, modeled after 401(k) plans in the United States, allow individuals to make voluntary contributions of up to 12,0000 yuan annually to supplement their public pensions.

According to Dr Huang, who is also affiliated with the Rutgers Center for Chinese Studies, the IRA is a personal savings account, and not social insurance, “because it has no social pooling or risk sharing among individuals”.

“By May 2023, more than 900 million households have participated in IRA, but the average savings put into it is less than 2,000 yuan per household.”

It’s clear that there’s more to be done, with experts emphasising comprehensive reforms being essential to ensure its sustainability, with proposed solutions spanning structural changes, fiscal reforms, and innovative labour policies.

Mr Frazier says the fragmentation in China’s pension system, with over 2,000 local governments managing funds independently, has led to administrative expenses being wasted.

“If you centralise or even bring it to 31 provincial-level pensions, then you’re going to save a tremendous amount of administrative costs,” he added.

The Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index 2024 suggests increasing the minimum level of support for the poorest individuals.

Another policy solution is to relax the country’s hukou household registration system, which experts say would improve eligibility and support for migrant workers and rural residents.

Meanwhile, China’s reliance on payroll taxes to fund pensions is increasingly unsustainable as the workforce shrinks.

To increase contributions to the pension pot, Ms Liu pointed to untapped revenue sources. “Right now, China doesn’t really have property tax, for example and I think capital gain tax in China is fairly minimal or is completely non-existent,” she said.

Dr Huang emphasised the urgency of broader fiscal measures. “The demographic crisis can easily turn into a fiscal crisis for the government,” he said. “Redistribution and changing the taxation system are crucial to managing these challenges.”

A more radical approach, as suggested by Mr Frazier, is to delink pensions from employment to create a universal basic pension.

“You have to consider ways to introduce reforms that would guarantee pensions for people in an economy in which, over 40 years, there may be 40 different jobs, 40 different employers,” he said.

China’s demographic decline has led others like Mr Poston to propose immigration as “the only answer” to replenish the labour force and alleviate pension funding pressures.

“China needs to turn to immigration to get them out of this quagmire. The country’s several attempts to implement policies to increase the birth rate have not worked, and they will not work.”

However, he also acknowledges the challenges. “It will not be easy to introduce and implement an active immigration policy in a country with little experience with immigration, few preferences for immigrants, and a seemingly deep-rooted belief in racial purity held by many leaders in the Chinese Communist Party.”

For millions of Chinese citizens, the stakes are high, and the path forward remains fraught with challenges.

“To be honest, I do have concerns,” said Ms Long.

“I worry that by the time I retire, there might be insufficient pension funds or a decline in the quality of services.”

“However, I hope the government and society will continue to address these issues and improve the system to ensure it remains reliable.”

Comments are closed.