CENTRAL JAVA: Rasjoyo could only watch in silence as his small wooden boat sailed through Semonet, a sleepy fishing village in the northern coast of Java he once called home.

The coast has receded about 1.5km inland in the last two decades, submerging 54 houses and hundreds of hectares of fish farms and rice fields. All of the land access to the now deserted village has also been cut off by brackish seawater.

“We used to have everything here in Semonet,” the 38-year-old, who like many Indonesians goes by one name, told CNA.

“We would catch crabs in the morning, tend to our fish ponds around noon and in the afternoon, pick flowers and fruits from our farms. You can say people here were quite prosperous.”

Then in the mid 2000s, the sea began encroaching the village.

Rice fields and farmlands were the first to be impacted as fresh water became more saline. Then the waves began pounding the row of houses, eroding the soft, sandy soil beneath them until these dwellings became one with the sea.

The community tried everything to stop water from entering their properties: Erecting walls of sandbags, building wave breakers out of rocks and concrete and raising their houses by up to 1m.

But these efforts proved too little too late to stop the forces of nature at play. By the mid 2010s, residents began to trickle out of Semonet. Rasjoyo’s family were some of the last people to vacate their properties in 2022, having lived further inland.

By late last year, the village was completely deserted.

What happened to Semonet – located in the Central Java district of Wonokerto – is not unique.

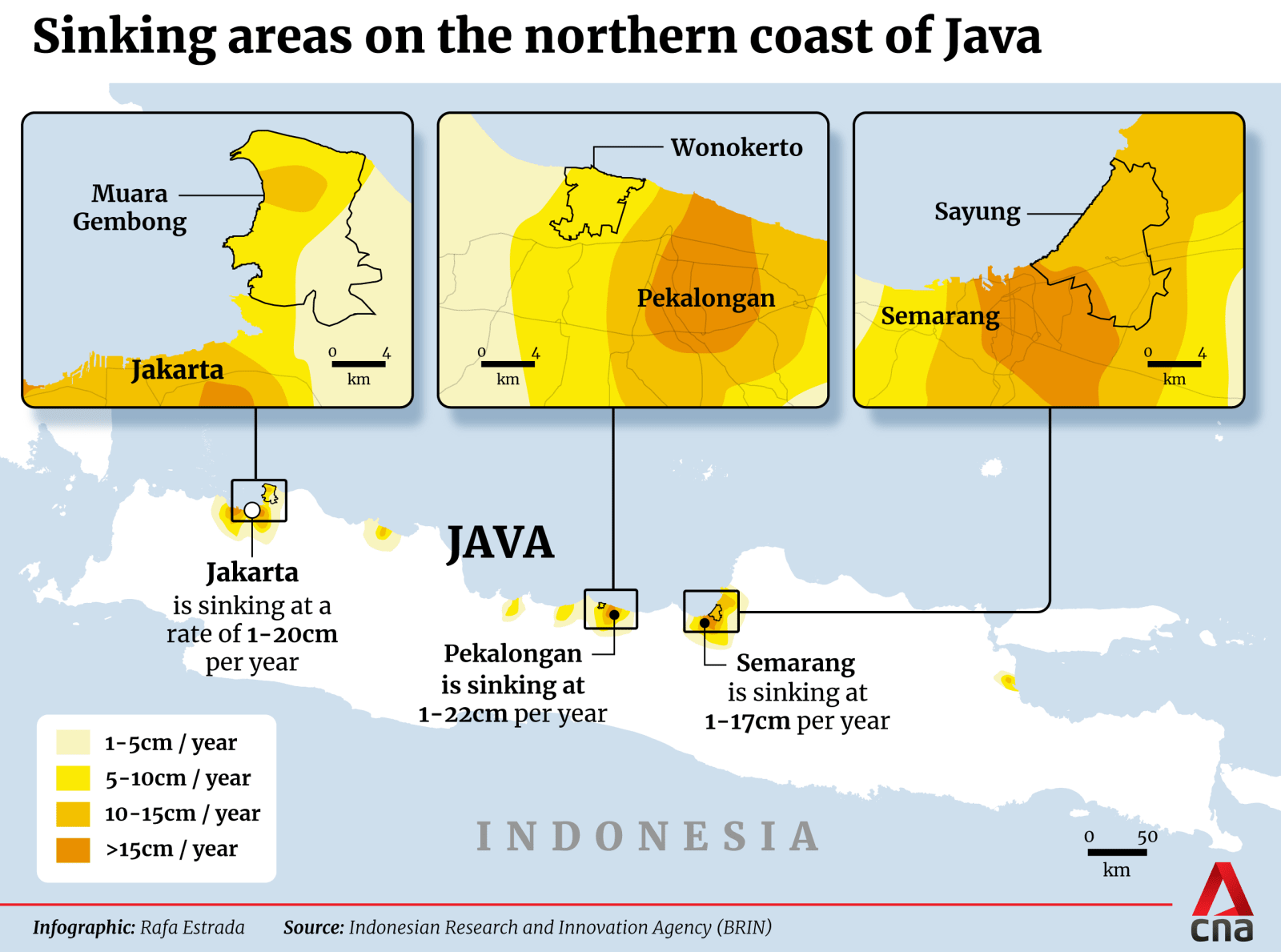

Along the northern coast of Java island, villages and urban communities are disappearing thanks to land subsidence, coastal abrasion and rising sea level.

In some areas, land has receded by more than 2km over the last 20 years, displacing thousands of people and causing millions of dollars in lost farmlands and residential areas.

Although these phenomena are also seen in the eastern coast of Sumatra and southern coast of Borneo, their spread and scale are nothing compared to what scientists are observing in Java, Indonesia’s most developed island where 56 per cent of the country’s 280 million population reside.

Unlike the hard, rocky soils of the south, the northern coast of Java sits largely on soft and unconsolidated sediments. Which is why cities like Jakarta, Pekalongan and Semarang, are sinking at a rate of between 1cm and 26cm every year.

The loose soils of these cities are compacted by the weight of man-made structures while the over-extraction of groundwater are causing ground level to recede as the earth beneath them deflates.

But while Jakarta, Pekalongan and Semarang have the budget and political clout needed to build coastal defences and other infrastructures to protect their inhabitants, the same cannot be said about small villages like Semonet.

“Unfortunately for sparsely populated villages, local governments tend to favour relocation instead of building expensive sea walls,” Heri Andreas, an expert on land subsidence from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), told CNA.

But Indonesia President Prabowo Subianto promised that this will no longer be the case, highlighting these coastal villages’ importance in the country’s food production.

Food security has become a key agenda for Prabowo, whose administration aims to achieve self-sufficiency for staples such as rice by 2027.

In February, the president announced that his administration will start building a giant sea wall which spans from Banten province in the western tip of Java to Gresik City in East Java. The two areas are 700km apart.

“A giant sea wall will save the northern coast of Java. A giant sea wall which spans from Banten to Gresik must be built,” the president said on Feb 25, as quoted by Kompas news portal.

“I don’t know how long it will take, but God willing, with strong determination, we will make it happen … We will start as soon as possible.”

But with the Prabowo government rolling out a number of austerity measures which saw the Public Works Ministry’s budget dropping from 111 trillion rupiah (US$6.7billion) to 50 trillion rupiah this year, it is unclear how this massive project will be financed, despite the president insisting that “the money is ready”.

Even if Indonesia manages to find the money, experts say that it will take many years before the sea wall is ready. Meanwhile, for coastal communities on the brink of disappearing, time is running out.

SAVING MILLIONS FROM FLOODING

About 7km east of Semonet, in the industrial city of Pekalongan, residents have to live in constant fear of rising sea level and tidal floods.

For decades, houses, businesses and farmlands relied on groundwater as nearby rivers have become polluted from the hundreds of batik factories and workshops dotting the city of 300,000 residents.

As a result, Pekalongan is sinking at a rate of up to 22cm a year with some estimates predicting that 90 per cent of the city will be below sea level by 2035.

When Nur Fatmawati bought her one storey home in 2018, her neighbourhood was at least 1.2km away from the sea, separated by rice fields and mangrove forests. Slowly, these rice fields were encroached by the sea before saltwater submerged rows after rows of houses and roads.

“Many people have moved out because their houses have been damaged by the sea. Tidal floods are becoming more and more frequent and inside my home water can reach up to here,” the 36-year-old told CNA while resting the side of her hand on the top portion of her stomach.

“That’s (the water level) inside my home. You can imagine what it’s like outside.”

With more than 40 per cent of its territory already below sea level, water had nowhere to go once Pekalongan got hit by heavy rainfall. The situation becomes worse when there is an occurrence of tidal surge or river overflow.

The same condition can be observed 80km east of Pekalongan in Central Java capital Semarang. The city of 1.7 million people is sinking at an average rate of 10cm per year with some areas already sitting 2m below sea level.

Flooding has become an annual fixture of Semarang, sometimes affecting more than 60 per cent of the city’s territory.

“Because much of our coastal areas are below sea level, we rely on dikes to stop the sea from flooding the city and pumps to get water from the rivers out to sea,” Mila Karmila, a city planning expert from Semarang’s Sultan Agung Islamic University, told CNA.

Central Java provincial secretary Sumarno, who also goes by one name, said billions of dollars have been earmarked and spent on building dikes, wave breakers and other infrastructures to save Pekalongan and Semarang from flooding.

Among them are a flood barrier to protect Pekalongan from sea surges and a 27km toll road spanning from Semarang to neighbouring Demak regency which will double as a tide gate.

The US$73 million Pekalongan barrier is scheduled to be operational this year while the US$918 million Semarang-Demak toll road is slated for completion in 2027.

These ongoing projects are the latest additions to various dikes, wave breakers and barriers meant to save Pekalongan and Semarang. Over time, these infrastructures – some of which are more than 20 years old – had become obsolete and needed to be reinforced and raised to keep up with the sinking land and rising sea levels.

“We hope these infrastructure projects can mitigate the issues of land subsidence and rising sea level plaguing Central Java,” Sumarno told CNA.

LIVING ON THE EDGE

The provincial secretary, however, said that there are areas like Semonet which are so devastated by sea intrusion the only viable option left is to relocate residents to safer areas.

Some 10km east of Semarang lies Rejosari village in Demak Regency. Two hundred families have abandoned their now sunken properties after the sea began encroaching their farmlands and homes in 2004. Over the next 20 years, saltwater has reached areas which are 4km away from where the coastline used to be.

Since 2010, Pasijah and her husband have been the sole inhabitants of Rejosari, residing in a dilapidated house on an increasingly dwindling patch of land surrounded by water.

“This is my home,” the 53-year-old told CNA when asked why she decided to stay in her village when everyone else had left. For Pasijah and her family, relocating meant abandoning the place where they had lived for generations.

“I want to protect this village from sinking. Which is why I have been planting mangroves. Even when the waves occasionally sweep away my mangroves, I am not giving up,” she said.

But her decision comes at a price. Electricity to the sunken village had long been cut off and buying groceries and other essentials involves a 40-minute round trip on a small wooden rowing boat to the nearest store.

During stormy nights, her house is pounded by giant waves, forcing the family to sleep on makeshift bamboo platforms tied to the wooden frame of her roof.

But Pasijah insisted on staying, even when her two sons, who had moved out to start families of their own, begged her to leave for her own safety.

“The waves are becoming bigger but so far I can still manage. As long as I am still healthy, able to plant mangroves and do my bid to save the village, I will stay,” she insisted.

About 3km northeast from Rejosari in the neighbouring village of Timbulsloko, resident Suratno is torn about abandoning a place where he was born and raised. The angry sea, which used to be a kilometre away, is now right at his doorstep.

“Moving to a new place is not that simple. I have been making a living from the sea, what am I supposed to do if I move inland? Suratno told CNA.

Timbulsloko used to be home to 400 families, of which only a quarter remains today. Some have learned to adapt to the encroaching sea by building their homes on stilts which rise about 1m from the water surface.

But with climate change bringing increasingly stronger winds and more unpredictable weather patterns, the waves are catching up.

“We sometimes had to evacuate and seek refuge at a mosque inland because the waves can reach up to two metres high,” Suratno said.

If the waves continue to get bigger and with his village sinking further, Suratno said he would have no choice but to leave.

“I want to leave but only if I had no other choice. For now, I can manage,” he said.

SHOULD A WALL BE BUILT?

Scientists estimated that at least 100 coastal areas along the northern coast of Java are on the verge of disappearing. This includes the country’s capital and biggest city, Jakarta, which experts predicted will have 95 per cent of its area sitting below sea level by 2050.

But experts are sceptical that building a 700km wall running almost the entire length of Java is the right solution to save these areas from sinking.

“Building a wall is a temporary solution,” said Mila, the urban planning expert.

Because the land is still sinking and sea level rising, such coastal barriers would still need to be raised and reinforced regularly.

“Semarang already has their own dikes and coastal defence systems in place but they cannot stop storm surges from flooding the city because like the land around them, these barriers too are sinking. So they are not long-term solutions,” she said.

Bosman Batubara – a researcher from the advocacy group Amrta Institute for Water Literacy – said building a wall also comes with great social and ecological costs.

“A giant sea wall will hinder thousands of fishermen from accessing the sea,” he told CNA, adding that there is also the chance that rubbish and other pollutants find themselves trapped inside the wall, posing a threat to the environment and people living in coastal areas.

The idea of building a giant sea wall is not new. The Indonesian government has been mulling the idea of creating a 30km long sea wall deep in the Java Sea for more than 10 years. However, rejection from local fishing communities and environmental activists forced the capital city government to put the plan on hold.

Indonesia’s Ministry of Public Works had previously estimated that it would cost 164 trillion rupiah (US$10 billion) to build the Jakarta sea wall.

To build a sea wall spanning almost the entire length of Java, as proposed by Prabowo, would require a budget many times larger, not to mention the various machinery needed to regulate water level as well as costs to operate and maintain it.

The Ministry of Public Works has not announced a detailed plan of the wall including whether ongoing projects like Semarang-Demak toll road-cum-tide gate would be a part of the system.

Heri of ITB thinks that the project should not be one contiguous structure but divided into several sections.

“There are areas which are not sinking because they sit on hard soil. Building a wall in these areas would be wasteful.”

And building a wall does not address the elephant in the room: Over-extraction of groundwater which causes land to subside.

“All that money should be more than enough to build reservoirs, water treatment facilities and water distribution networks which are necessary to stop people from relying so much on groundwater,” Heri said.

But Sumarno – the Central Java provincial secretary – said getting people to stop using groundwater is not that easy.

“We are barring new industrial areas from using groundwater. But we need to work with existing (industries and households) which have for years relied on groundwater. We cannot stop them without first offering alternative sources of water,” he said.

“It takes time to build dams, reservoirs and distribution networks and once they are ready then we can start reducing the use of groundwater.”

People living in affected areas are also unsure about the plan to build a giant sea wall off the northern coast of Java.

“What matters is that we can still fish at sea and earn a living. I hope the government will take that into consideration when designing this new wall because we have lost so much and we need to rebuild our lives again,” said Semonet resident Rasjoyo.

“I hope there are lessons the government can learn from what happened to our village and take what they learned so other villages don’t suffer the same fate. Otherwise, our sacrifices will be in vain.”