ULAANBAATAR: In the early 13th century, after uniting the nomadic Mongol tribes, the ruler Genghis Khan searched far and wide for a sacred centre for his sprawling empire.

He had a shamanic vision, according to Mongolian folklore, that told him of a blessed valley that lay under the gaze of the Eternal Blue Sky, the divine protector of his people.

That place was the Orkhon Valley, a wide windswept plain dwarfed by the immense sky that defines Mongolia’s landscape until today. It had been hallowed ground for centuries and a home to preceding ruling cultures.

What began as a strategic command post on the crossroads of the Silk Road evolved over time into something grander and more permanent: Kharkhorum, a cosmopolitan city of traders, artisans and treasures.

Within a few decades, Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis, would uproot the city, moving the empire’s centre of power closer to China, in Ulaanbaatar.

With that, Kharkhorum would sink back into the earth, its palaces buried by time and the sands swept across the steppe. But the memory of this place still lives on. And now there are efforts to turn it into a new capital city for the Mongolian people.

The country’s leaders have drawn up a US$30 billion blueprint to return the nation’s centre to its ancestral heart. The project to rebuild “New Kharkhorum” as the future new capital is also designed to relieve the pollution and congestion in the current capital Ulaanbaatar.

“The original Kharkhorum was the world’s centre of culture, politics, religion, and economy – comparable to how New York serves as a global hub today,” Khaltar Luvsan, the mayor of Kharkhorum City, told CNA from a modern office building in Ulaanbaatar, where dozens of architects and engineers are piecing together the new city plan.

“What we aim to do now is to merge that historical identity with modern principles of smart and digital cities,” he said.

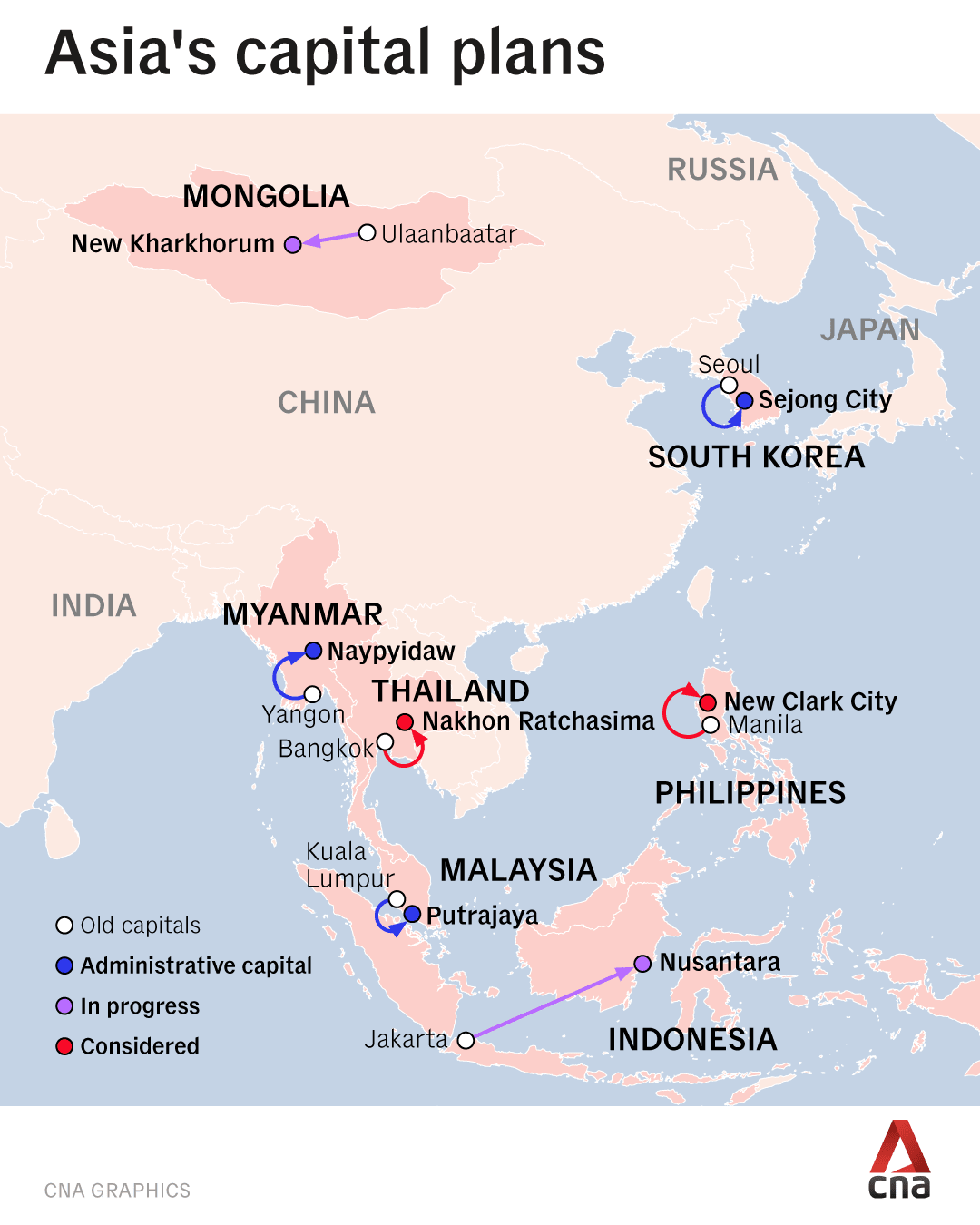

A reborn Kharkhorum, which lies about 350 km west along a potholed highway from the current capital, is only the latest chapter in a long-running regional story.

Across Asia, various governments have attempted to redraw their maps by shifting their capital cities, bets that analysts say are designed to fix old failures, spread prosperity and project crafted visions of power.

In the past, it was a decision made in countries like Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

More recently, from the jungles of Borneo to the floodplains of the Chao Phraya, the idea endures: When a country runs out of room or into crisis, it debates building somewhere else.

Indonesia is partway through shifting its government functions to a jungle metropolis called Nusantara, with Jakarta facing a litany of urban issues.

In Thailand, the country’s interior ministry earlier this year examined the merits of moving its capital away from the rising sea levels and annual sinking impacting Bangkok.

South Korea is pushing its administration out to a project called Sejong City, while in the Philippines, the development of New Clark City has long been considered part of a long-term decentralisation plan to ease congestion in Metro Manila, and potentially act as a back-up capital in the event of a disaster.

Like Indonesia – and others around the world like Egypt, Equatorial Guinea and South Sudan – Mongolia is looking to build a new hub centred around sustainable virtues: Something that is walkable, liveable, green and smart. Something born on paper for the generations of tomorrow.

“What makes it so appealing is that you have this image of a blank slate and that is such an attractive, simplistic idea,” said Natalie Koch, a political geographer and professor at Syracuse University in New York.

But behind the green slogans and shiny promises, a more complex story unfolds. In some cases, it includes elements of elite aspiration, speculative investment and the uneasy trade-off between symbolism and substance.

History shows that capitals rarely move as neatly as their planners imagine. From Abuja in Nigeria to Dodoma in Tanzania, Astana in Kazakhstan and Naypyidaw in Myanmar, many new capital cities in the last three decades have been left a shell of their ambition.

“Buildings on a blank slate, it’s a lovely image, but it doesn’t solve any of those bigger structural issues in a state,” Koch said.

The same questions that confronted other leaders as they built their modern utopias are now being faced by Mongolia’s as well.

MONGOLIA’S MANDATE TO SHIFT

Despite being in the least densely populated country on earth, Mongolia’s capital feels suffocating. Fierce traffic snarls punctuate the start and finish of every day.

As winter approaches with its bitter cold, the country’s coal fleet fires up, enveloping the Tuul River valley in a noxious black haze that lingers for months.

“It’s a city that smothers you and tries to kill you. It’s very inhospitable,” said Battushig Togtokh, the social enterprise lead at Gerhub, a sustainable urban transformation organisation in Ulaanbaatar.

The city presses against its own borders, hemmed in by four encircling mountains. In the outskirts, sprawling districts of gers – traditional Mongolian tent dwellings – test the government’s abilities to deliver essential services like water and waste removal.

A place designed for a quarter of a million people now struggles to contain six times that number, with about 1.6 million people living within 35 sq km designated for residential land in Ulaanbaatar.

That is half of Mongolia’s population packed into an area that makes up less than one-thousandth of a per cent of the country’s land.

Call it “extreme population density”, said Oyunbat Bataa, director of urban planning for the Kharkhorum City mayor’s office.

“Everyone knows that Ulaanbaatar is struggling, with traffic congestion, air pollution, soil contamination and overcrowding. To put it simply, people are social beings. When all social and economic opportunities are concentrated in one place, like Ulaanbaatar, it’s only natural that people will be drawn there,” he said.

The New Kharkhorum project is presented as a fix for Ulaanbaatar’s failings.

According to the long-term government plan, by 2050, Mongolia’s population is expected to reach 5 million and about 10 per cent of that population is to be located in the Kharkhorum region, envisioning a city of around 500,000 people.

Once the city’s master plan is completed and approved by the government, which is expected to take 12 to 18 months, Luvsan said, it will move into full-scale implementation with the goal of housing up to 30,000 residents within a decade.

Connecting the region will be one of the initial challenges, with plans to construct upgraded road and railway connections and an international airport.

The new capital design also includes a proposed full-scale agricultural cluster, the phased restoration of ancient lakes and excavation of the original Kharkhorum, to be transformed into an open-air museum that can attract both domestic and international visitors.

This forms part of a strategy “to create a transnational tourism belt that connects Russia, China, Asia and Europe, through Mongolia”, Luvsan said.

The first landmark site is already under way in the form of the Great Khans’ Park, a memorial garden dedicated to Mongolia’s great rulers, alongside 700,000 newly planted trees.

The city planners say businesses, social services, health infrastructure and education providers will follow as New Kharkhorum grows, outfitted with technology and anchored in sustainability.

“Naturally, building a city from scratch in an empty field is difficult to imagine at first. But we have dreams, we have goals and we’re determined to make it happen,” Luvsan said.

LESSONS FROM INDONESIA AND ITS FUTURE CAPITAL

The dream of New Kharkhorum may be uniquely Mongolian but its challenges are familiar. Others in the region have walked this same path before.

Decades before former Indonesia President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo declared plans for Nusantara as its new jungle capital, the country’s founding leader Sukarno had imagined something similar.

He had grown disillusioned with Jakarta, a crowded relic of the colonial era. Instead, the city of Palangkaraya in Central Kalimantan was to consolidate the spirit of the nation in the geographical centre of its archipelago.

The city was built, but the grand plan that inspired it never materialised.

When Jokowi announced East Kalimantan as the location of Indonesia’s new capital in 2019, while the location may have been similar, the vision was entirely different, said Anders Kirstein Møller, a researcher who recently completed a PhD in urban geography at the National University of Singapore.

“Sukarno may have been an idealist, in some sense, but he was a classic post-colonial, anti-colonial idealist who just wanted material development for the country and to shift away from the political and infrastructural legacy of the colonial era,” Møller said.

“For Jokowi, it’s all about modernist, high tech, idealistic development.”

Nusantara’s fundamentals have led to a “fragile” project that has no common agreement on what the city is actually symbolising, prioritising, promoting or creating, he argued.

Nusantara was envisioned to be a green and smart city that would serve as a technology testing ground and achieve net zero emissions by 2045.

The many buzzwords and concepts swirling around the projected have created a “black box for policy”, Møller said, that will eventually lead to disappointment when people don’t get “that utopian, civilisational progress that they were promised”.

The initial cost for Nusantara was cited at around US$32 billion, according to Indonesian government planning documents. Vast private investment will be required to cover about 80 per cent of the bill. It was projected to house up to 1.9 million residents by 2045, with civil servants and other officials relocating from Jakarta to work there.

Nusantara is very much underway, but still early in its build-out. Some key elements exist or are being built, while many other aspects remain in future plans.

Its progress has been hampered by inflating costs, logistical issues and shifting political priorities.

In September, it was made public that Nusantara’s status had been downgraded from “national capital” to “political capital” under President Prabowo Subianto.

TO MOVE OR NOT TO MOVE?

While Indonesia grapples with the future role of Nusantara, its neighbours are surely watching.

Bangkok and Manila, two coastal megacities like Jakarta and the power bases of their respective nations, also face questions of viability for the coming generations.

The Thai capital is precariously close to sea level – just 1.5m above currently.

Little now separates the rising sea from Bangkok’s endless sprawl of roads, factories, malls and high-rises – a city whose own weight is causing the land beneath it to sink by as much as 2cm a year. A city made by water faces being swallowed up by it.

“I am scared because there’s nothing that can fend it off,” said Sinsamut Phuttameephol, a 64-year-old fisherman living close to the Gulf of Thailand.

With those concerns in mind, a quiet political debate has been simmering for a couple of decades in the country about the prospect of shifting the government away from Bangkok.

In the early 2000s, the government under Thaksin Shinawatra assigned its economic planning agency to study relocating the capital to Nakhon Nayok, about 100km northeast of Bangkok.

When major flooding overwhelmed Bangkok in 2011, the issue of a move to inland safety was raised again. In 2019, it was publicly floated by then Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha as a decongestion measure.

This year, after a lawmaker had proposed in 2023 shifting the capital to Nakhon Ratchasima province, also in the north-east, a House committee within the Interior Ministry concluded such a move would be too costly and would require a referendum. Instead, it recommended more protection for Bangkok, including sea barriers.

The committee did not extinguish the relocation idea though; it called for comparative studies of other countries that have relocated capitals to better understand the challenges.

While the city faces an existential risk, landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom, chief executive and founder of Landprocess and Porous City Network, a social enterprise focused on urban issues in Southeast Asia, argued that resilience should come before retreat.

“We need to adapt rather than move,” she said, describing a metropolis that can thrive around water rather than running from it. “Let’s make the water reunite us rather than making us very fearful.

“From the history of Bangkok, we are amphibious. I feel it’s so possible to live with the flood. And even if you move your capital, you still need to fix Bangkok problems,” she said.

Manila too faces land subsidence issues, as well as flooding and storm surges, overcongestion and the everpresent exposure to earthquakes.

Likewise, successive governments there have been looking inland for potential relief.

Philippine historian Michael Pante, an associate professor at Ateneo de Manila University, has watched New Clark City slowly expand its foundations about 100km north of Metro Manila.

The site of a former American air base was pitched in 2018 as a disaster-resilient backup hub. But with a completion date set for 2065, a potential future population of 1.2 million people and having attracted by mid-2024 nearly US$2.5 billion in investment, it represents far more than a contingency plan.

It is being conceived as a “smart city” with sustainable urban planning principles, a disaster-proof government administrative centre and an already-functioning international airport, all 60m above sea level.

Still, Pante labelled the government-supported but privately-built and commercially-driven new city more a refuge than a replacement for the capital.

The considerations now in the Philippines are more practical than symbolic – safeguarding governance and driving investment – unlike in the past, he said.

For many years, Manila struggled to shake its colonial lineage. Indeed the Philippine capital was shifted to Quezon City shortly after the country gained its independence in 1946, in an attempt to forge a new identity.

It lasted as the capital for nearly three decades before being moved back to Manila and the urge to shake off the connections to the past has since diminished, Pante said.

“There’s no really serious attempt at trying to position Clark as a city that would supplant Manila, but more of a city that could support it and supplement it, given that Manila cannot provide basic services to all its residents at an adequate level,” he said.

“If Clark can generate a good number of jobs, then okay. But that shouldn’t come at the cost of, for instance, people being displaced in their own ancestral land or the government using it as a kind of justification to just let Manila sink,” he added.

QUESTIONS OF LEGITIMACY AND LEGACY

The decision or debate around building a new capital is often framed as a public good, as a fix to existing problems, to fight back against the changing climate and advance national progress.

But Koch said her research has found it is also about who controls the narrative, who profits from the contracts and who cements their legacy.

These are the types of prevailing issues with new capitals that she has studied extensively in other parts of the world. And where there are projects that have failed, the money trail too often leads back to a leader or a government looking after elite allies, she said.

“I think, the most important thing to keep in mind when evaluating whether a capital city is successful or not, is to actually ask, ‘for whom is it successful?’,” she said.

“More than anything, it just seems like most of these projects in democratic and non-democratic countries are just elite money grabs. And why so many remain empty is simply because the people who mattered got paid already and they really don’t care.”

In Indonesia, as Marcus Meitzner, associate professor in the Department of Political & Social Change at the Australian National University noted, some have argued the Nusantara project became more of a personal legacy project than a shared national agenda.

“Jokowi viewed Nusantara as his primary legacy. For him, it symbolised his political boldness. But for his critics, it reflected his recklessness and disdain for careful planning,” he said.

The former president’s decision created what Meitzner called “an ineffective hybrid”, pushed hard by one leader, inherited by the next. To be effective, he said, “it would require an elite consensus. This has been lacking in the case of Nusantara from the beginning”.

While Prabowo has reaffirmed his commitment to Nusantara, his government has laid out eight national priority programmes for 2026, including food security, energy resilience, education and defence, but notably not specifically the new capital.

Because of Prabowo’s reticence, as well as other issues like its location and planning, Benny Subianto, a programme consultant at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, said he expects Nusantara to become either a “city of bureaucrats” or a “ghost city”.

“I really doubt that Nusantara will become a functioning symbol of renewal. It’s likely to become a stalled project,” he said.

In Mongolia, Togtokh has concerns about the government’s ability to deliver New Kharkhorum, a project of great scale that will need to attract large amounts of public and private finance.

Public confidence in the government has been rocky in recent times. In June, then-Prime Minister Luvsannamsrain Oyun‑Erdene was forced to resign after losing a parliamentary vote of confidence, which followed large youth-led protests over allegations of graft.

Mongolia has deep structural issues related to corruption. It ranks 114th in the world on Transparency International’s corruption perception index, which found that 69 per cent of Mongolians surveyed believe government corruption is a “big problem”.

In March this year, the United Nations Human Rights Committee questioned Mongolia’s “widespread and deeply-rooted corruption, particularly high-level political corruption cases” and expressed concerns about the lack of systematic enforcement of anti-corruption laws.

“Creativity is not at a loss here. We’re in shortage of morality, and especially procedural morality and ethics,” Togtokh said.

“When that’s in shortage and nothing can get done, no amount of planning and fancy keywords and sex appeal and aesthetics and tacky design can get you anywhere,” he said, referencing the plans for the new capital.

Luvsan acknowledged the great challenge ahead, but said he was confident that the government and people of Mongolia were behind New Kharkhorum.

“The success of any project depends on the quality of its planning. If the planning is solid, the project will succeed,” he said.

THE TWO-CAPITAL TRAP

Around the world, a structural trap that haunts many relocations is the “two-capital” dilemma. Governments move ministries but not markets, and parliaments but not people.

In Kazakhstan, the quest to legitimise its new capital, Astana, has been a long and uneasy process. Naypyidaw too, another city dropped into the relatively obscure but strategic heartland of Myanmar, has for decades failed to capture the life and culture of Yangon.

The seat of the Malaysian government was moved to Putrajaya in 1999 to serve as the country’s administrative capital and ease congestion in Kuala Lumpur. Its 35km proximity from downtown KL has meant it remains in the orbit of the city it was designed to relieve.

Other established capitals like Canberra, Islamabad and Brasilia are functioning, liveable cities but took decades and expenditure in political capital to establish themselves.

That is an investment that may come at a cost to existing places, according to Moller, and should be considered by those eyeing such projects.

In many of the current capital cities, issues such as air pollution, traffic congestion and flooding still require funds and the attention of policymakers to tackle.

“If you’re spending so much time and energy on this very challenging project, you literally, you physiologically, cannot spend it on trying to fix other smaller, less sexy policy problems,” he said.

As Chintan Raveshia of Arup noted, if phase one of a new capital does not get the fundamentals right – namely the governance, transparency and environmental framework – “you’re going to have a massive problem legitimising the city for another 20 years to come”.

“The most difficult thing for a new capital city is that it doesn’t have any memory. And memory is what makes cities,” said Raveshia, who leads the cities, planning and design business in the Asia-Pacific region for Arup, a global planning, design and engineering consultancy that worked on Nusantara.

“And when you don’t have that generational aspect of memories, a sense of ownership doesn’t exist.”

Raveshia said that real sustainability demands designing with nature, an approach that unfolds slowly, through care and connection rather than quick construction.

Yet, even as planners promise sustainability, the act of building anew is rarely gentle. In Nusantara, thousands of hectares of tropical forest were cleared to make way for a city designed to be “net-zero”.

“Using environmental reasons is never a good reason to build a new city. These projects are incredibly destructive,” Koch said.

For local people in the Orkhon Valley, there is a mixture of hope and hesitancy about what lies ahead. Rich in history, the area has faced a lack of development for centuries.

“I believe they can turn this place into a proper, beautiful city in a short time. That’s what I really wish for,” said Ganbat Sandag, a local market stall owner.

“It’s such a unique and historically rich place,” said Saraa Banzar, who owns a souvenir shop near the Erdene Zuu Monastery, built on the site of the old Mongolian capital.

“I hope Mongolians can make it happen. But honestly, I’m not sure,” she said.

Standing on the exposed plains of the old Kharkhorum, where grass now covers the stones of the old empire, it is impossible not to wonder what kind of footprint the next city here will have.

Additional reporting by Khaliun Amarsaikhan

Comments are closed.