Commentary

Great powers have always pursued their interests at the expense of smaller states, but the brazenness on display now is striking, says Patricia M Kim from the Brookings Institution.

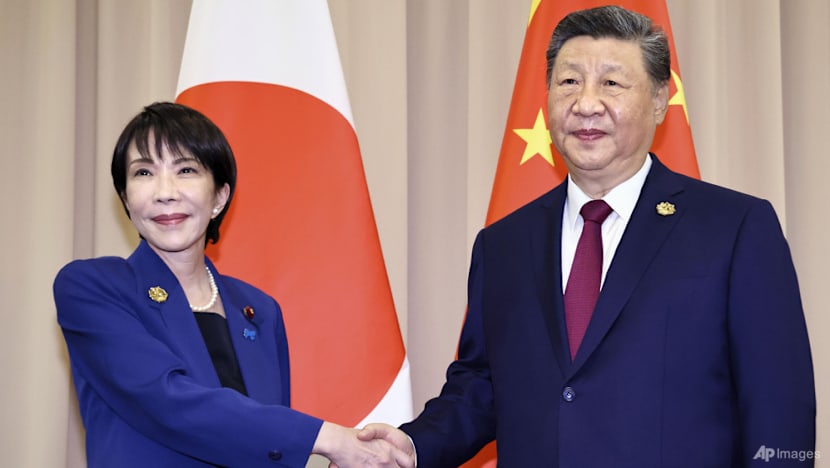

Chinese President Xi Jinping shakes hands with Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi ahead of their meeting in Gyeongju, South Korea, Oct 31, 2025. (File photo: Kyodo News via AP)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

09 Dec 2025 06:00AM

WASHINGTON DC: After Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s warning in November that a Chinese attack on Taiwan would pose an “existential threat” to Japan and that Tokyo may intervene militarily in response, Beijing reacted with a familiar mix of diplomatic fury and economic pressure.

Then came a second shock: Rather than rallying behind its formal ally Japan, United States President Donald Trump reportedly urged Ms Takaichi to dial down her rhetoric after he spoke with Chinese President Xi Jinping, concerned that tensions over Taiwan would jeopardise US trade negotiations with Beijing.

Though Tokyo later denied that Mr Trump had issued such a request, Japanese officials have reportedly expressed frustration at the lack of stronger support from the Trump administration.

While US Ambassador to Japan George Glass publicly denounced China’s actions as “provocative” and “coercive”, and reaffirmed Washington’s “unshakable” commitment to the US-Japan security alliance of nearly eight decades, that message has not been echoed at the top. It suggests that the Trump administration is placing more weight on other considerations.

Taken together, these reactions highlight an unsettling feature of today’s geopolitics: Great powers are increasingly willing to shape events to suit their own aims, even when doing so leaves counterparts exposed. In both Beijing and Washington, leaders are approaching the dispute with their narrow interests at the forefront, assuming states reliant on them for economic stability or security will ultimately adapt.

The result is a global arena defined less by shared rules and norms than by unabashed power politics – and the uncomfortable reality that Japan has ever less room to manoeuvre as Beijing presses its demands and Washington prioritises its own objectives.

CONFRONTATION, NOT CHARM

China’s retaliation against Japan since the dispute erupted has been swift and multifaceted, making clear that Tokyo had crossed one of its most sensitive red lines.

The government has halted group tourism to Japan, reimposed bans on Japanese seafood imports and sent letters of complaint to the United Nations.

Chinese media has amplified pressure with sharply-worded denunciations, accusing Ms Takaichi of pushing Japan down a “perilous path of militarism and war” and urging her to “repent and change course”. One Chinese diplomat went so far as to call for “cutting off” the “filthy neck” of the Japanese leader on X.

Japan recently issued a safety advisory for its citizens in China, citing “anti-Japanese sentiment” ahead of the anniversary of the 1937 Nanjing Massacre.

China’s response reflects a broader shift in Beijing’s diplomacy in recent years. Facing Western export controls, rising scrutiny of its global economic practices and criticism over its deepening ties with Russia, China has embraced a posture that rejects external pressure outright.

Charm is out; confrontation is in.

Its leaders now increasingly operate on the assumption that China possesses the economic weight and structural leverage to impose its preferences, controlling critical chokepoints – from rare earths to pharmaceuticals to advanced battery materials – that allow it to inflict real economic pain on neighbours that dare to challenge its core interests. While Beijing’s use of economic coercion is hardly new, its approach in the current trade war with Washington has only reinforced its confidence in such tactics.

By taking a hardline stance and deploying sweeping export controls, Chinese officials believe they compelled the United States to ease its position. The lesson, in Beijing’s view, is clear: There is little incentive to soften its behaviour when coercion delivers results.

AMERICA MAY NOT ALWAYS CHOOSE THE SIDE OF ALLIES

The American response has been uneven and at times contradictory.

After his call with Mr Xi, strikingly, Mr Trump’s subsequent Truth Social post offered no support for Tokyo, no criticism of Beijing’s behaviour, and no mention of Taiwan. Instead, he praised a “very good telephone call” with Mr Xi, touted Chinese soybean purchases and highlighted his planned visit to Beijing in April 2026.

Whether Mr Trump really did press Ms Takaichi not to provoke Beijing or not, his silence left little doubt: Washington is willing to look past China’s coercive behaviour – even when directed at a close ally – to avoid complicating its own dealings with Beijing.

That stance sits uneasily with longstanding American efforts to encourage Japan and other allies to shoulder more responsibility for regional security.

For Tokyo, the implication is unmistakable: When Washington must choose between alliance solidarity and transactional gain, it may not always choose the former.

BRAZENNESS ON DISPLAY

What is unsettling for Tokyo – and likely many of its neighbours – is that this dynamic reflects a broader shift in great power behaviour. To be sure, great powers have always pursued their interests at the expense of smaller states, but the brazenness on display today is striking.

Beijing and Washington may rely on different instruments, yet both are increasingly willing to press their preferences and expect others to adjust. China leverages its market size and supply-chain dominance to enforce its will; the United States deploys tariffs, its still-formidable economic weight, as well as its central role in the region’s security architecture to shape outcomes to its favour.

In this new environment, Japan is hardly alone. Across the Indo-Pacific and beyond, governments are undoubtedly reassessing their ties with both great powers.

The China–Japan dispute, and Washington’s response, is less an anomaly than a reflection of a more volatile, transactional era – one in which reassurance is selective, pressure is routine and great powers feel fewer constraints on their behaviour.

US partners can no longer assume dependable solidarity from Washington, just as China’s neighbours cannot count on reliable economic engagement from Beijing. These trends will only accelerate efforts by all states to diversify their trade ties, build redundancy into their supply chains, strengthen inter-regional cooperation and invest more seriously in their own defence capabilities.

The message resonating across Asia is clear: In an age of renewed great-power assertiveness, relying too heavily on any single patron – whether Washington or Beijing – has become a strategic risk in itself.

Patricia M Kim is a Fellow with a joint appointment to the John L Thornton China Center and the Center for Asia Policy Studies at the Brookings Institution.