Sylvia Yu Friedman still vividly remembers her brush with death in 2012, more than a decade ago.

Then a young journalist and filmmaker, Friedman had travelled to a red-light district outside the city limits of southern China to capture footage of underage girls in the sex trade for a documentary.

“The alley was pitch black, no street lamps. There was a low building with sliding glass doors, large windows and pink light.

“There were women in makeup and short skirts looking sad, and thugs with pasty white faces milling around. Vicious dogs were barking. You could palpably feel the ickiness and the danger,” she recounted.

A frontline worker who accompanied Friedman advised her to walk through the alley, pretending to be a tourist and surreptitiously film the scene on her mobile phone.

Friedman’s gut instinct told her she would never get away with it – no female tourist was seen in this part of the country. But so determined was she to get the footage that she hushed her inner voice and braved the walk through the dark alley.

With the footage in hand, she hastened to the getaway car.

In a heartbeat, thugs and mamasans surrounded her, shouting menacingly and demanding to see her phone. Shaking with fear, Friedman deleted her footage, but they did not let her leave.

“I was so scared,” she said. “Just when I thought I was going to get hurt and saw my life flash before my eyes, suddenly, one of the thugs said the police were coming and they scattered like cockroaches when you shine a light.”

That night, Friedman screamed in her room from the terror and trauma. Her post-traumatic stress disorder lasted for months and she had to seek counselling, she told CNA Women.

The deleted footage, however, remained in her trash folder, and became part of Friedman’s three-part documentary series about human trafficking in China, Hong Kong and Thailand. This series won the English-Language Television Merits prize at Hong Kong’s 18th Human Rights Press Awards in 2013.

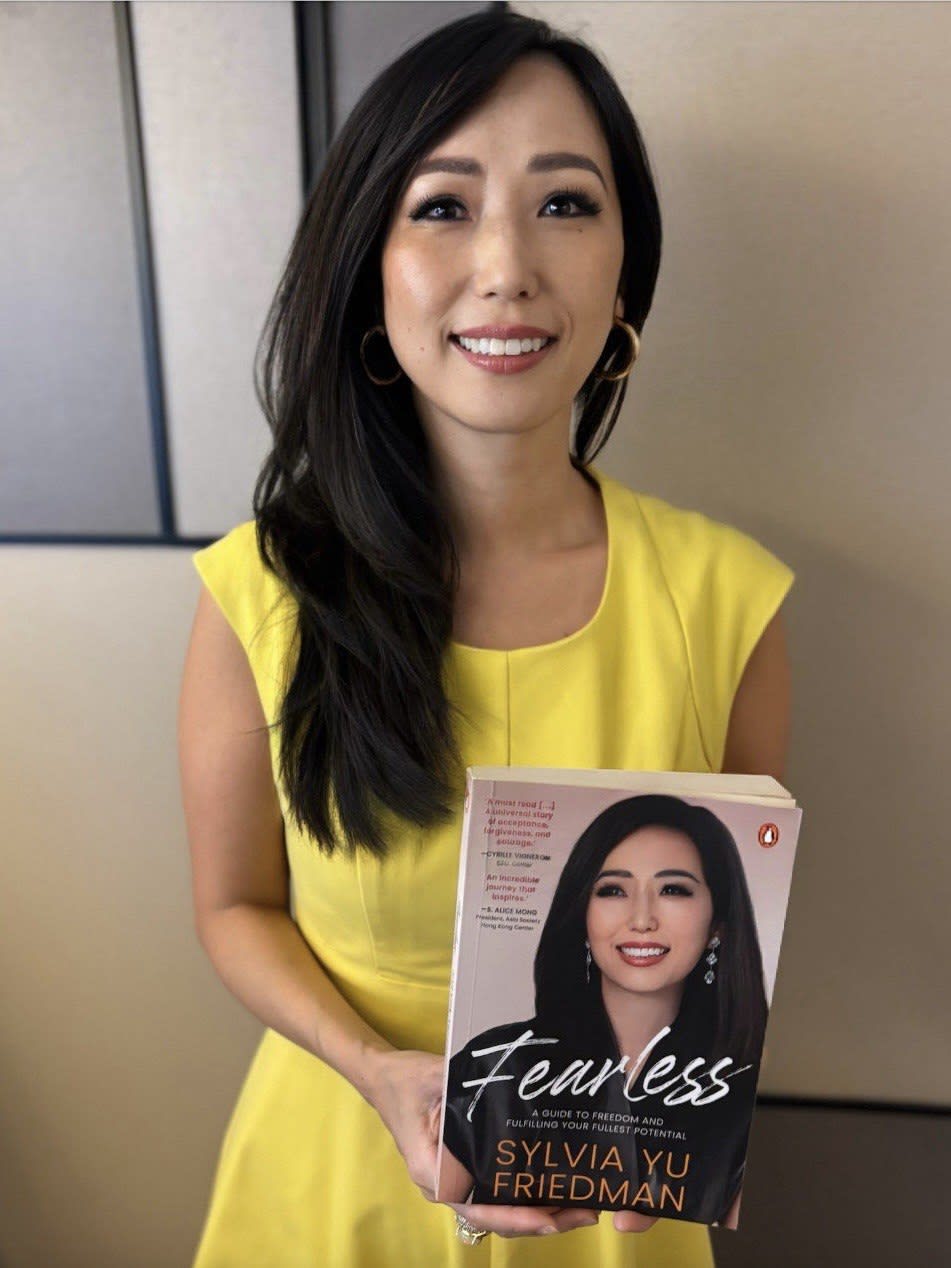

Friedman retells some of these experiences in her memoir Fearless, published in October 2024. In an interview with CNA Women in the same month, she gives a glimpse into the clandestine world of human trafficking and the sex trade.

UNEXPECTED FORK IN HER JOURNALISM CAREER

Meeting the Korean-Canadian for the first time, you would not have guessed she once braved the dangers of the seedy underworld. Now the director of a private equity firm, the 40-something author strikes me with her feminine demeanor, underscored by a quiet strength.

She told me that in 2001, as a young TV journalist in Canada, she found out from an activist that an 80-year-old Korean survivor of Japanese military sexual slavery, Kim Soon-duk, would be sharing her experiences in Washington, DC.

On impulse, Friedman bought an air ticket to the United States to interview her. It was so impromptu that she almost missed Kim and ended up interviewing her in a train station.

That interview changed Friedman’s life.

Kim told Friedman she had been lured into a military brothel in Shanghai, China, with the promise of a nursing job. There she became a “comfort woman”, a euphemism for forced prostitution. For three years, she was repeatedly raped by Japanese soldiers.

At that point, the Japanese government was denying or downplaying the existence of comfort women like Kim, and there was a lack of English language material on this dark chapter of history, Friedman said.

Inspired by Kim’s courage in sharing her horrific story, Friedman felt compelled to tell the story of other comfort women.

In 2004, she flew to Beijing, China, to work as a freelance journalist and over the next decade, interviewed some 15 comfort women in their eighties and nineties who had been repeatedly raped by as many as 30 Japanese soldiers each day.

The trauma remained fresh for these women even 50 to 60 years later, recalled Friedman. “One mainland survivor in her mid-eighties fainted when she was recounting her story,” she said.

A VOICE FOR THE VOICELESS

Her work with comfort women led Friedman to investigate the trafficking world and modern slavery. Over the years, she has spoken to some 40 women, including trafficked brides and sex workers.

“I began to see there was a cycle that was repeating – women’s voices are often ignored, silenced, whitewashed,” she said.

Friedman began working as an advisor to philanthropists to direct funding towards anti-trafficking projects, HIV/AIDS initiatives, migrant slums, education programmes for kids and job training for trafficking survivors, she said.

Through her work, Friedman encountered many unspeakable tales of horror, such as the story of Mei, a 19-year-old woman from China whom Friedman met in 2011.

Mei had been trafficked as a child bride at the age of 14, bought by a farmer in his seventies, and chained up like a dog for years. She later bore this man a daughter, whom she was forced to abandon to make her escape.

Her freedom was shortlived. Preying on her vulnerability, a female trafficker lured her to work in a brothel where she contracted HIV before she was eventually rescued and housed in a shelter.

Finding women like Mei who are willing to speak up was extremely challenging, said Friedman. In her journalistic career, she has scoured gritty backstreets and buildings with one-room brothels for months in search of a lead.

Even when Friedman found them, the victims were not always willing to talk. Some were overwhelmed with shame and bitterness. Their eyes had glassed over, and they had numbed themselves to cope with the indescribable pain and horror, Friedman said.

But those, such as Kim and Mei, who did break their silence, had beseeched Friedman to share their story with the world. And she has made it her mission to do so, writing many articles and publishing books to bring their stories to light over the years.

ADVOCATING FOR CHANGE

What is shocking is that human trafficking and modern-day slavery is still happening today.

In her 2021 book A Long Road To Justice: Stories From The Frontlines In Asia, Friedman wrote about North Korean women who attempted to escape a harsh regime via the “Underground Railroad”, a network of people, safe houses and routes, only to be trafficked to China into forced marriages or sexual exploitation.

Between 2017 and 2018, Friedman also wrote news articles about Indian and Pakistani women tricked into arranged marriages only to find themselves indentured labourers and servants for their in-laws, as well as Indonesian child maids in Hong Kong and Singapore.

“I want to raise awareness because the same cycle of slavery and exploitation is still happening,” Friedman said.

She hopes increased awareness will mobilise the public, non-profit organisations and activists to help victims, and also deter men from frequenting red-light districts.

The ex-journalist also rightly pointed out that financial hardship, and the lack of education and work opportunities are often what led victims to leave their countries and take risks others normally wouldn’t in the first place, making them vulnerable to human trafficking and exploitation.

“I’ve interviewed women who were forced into sex work in the beginning, but near the end, they just became numb, and it became a way to finance their life, their families,” she added.

Friedman hopes more can be done to address these systemic issues. “It could have been you or me had we been born in these circumstances,” she said.

Speaking to educated and empowered women, Friedman said: “I want to encourage women not to get so comfortable, but to use your time, talents and influence to help the marginalised and vulnerable.

“Learn about it, get to know a local non-profit that’s helping women who are exploited, raise awareness in your circle, give talks on it, help these women with job training,” she said.

“There’s no secret to a happy life. We all have challenges. But the secret to a fulfilled life that is closer to happiness and contentment is serving others and helping others,” Friedman added.

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg.