BEIJING: US President Donald Trump’s pledge in his inauguration speech on Monday (Jan 20) to enlarge American territory, specifically on retaking the Panama Canal, has deepened concerns that he stirred up only recently over his expansionist agenda.

“The United States will once again consider itself a growing nation, one that increases our wealth, expands our territory, builds our cities, raises our expectations and carries our flag into new and beautiful horizons,” Trump said in the US Capitol in Washington DC.

While Trump did not reiterate his intent to grab Greenland, observers believe such a move remains possible and could spur increased rivalry with China and Russia in the Arctic by turning the region from an arena of climate change to a zone of militarisation and possible confrontation.

They add that the renewed rhetoric by the newly minted US president could push China closer to Russia in the Arctic as Beijing works to overcome limited access in the region and keep its strategic interests afloat.

“(China and Russia) will become even more tied, to kind of unite together to compete or fight back against Trump’s US in the Arctic,” cautioned Liu Nengye, an associate professor of law at Singapore Management University (SMU) specialising in polar law.

With China under no illusions about the deep freeze in Sino-West polar cooperation, analysts anticipate security to take pride of place in Beijing’s evolving Arctic strategy.

“I think China’s language is going to be considerably more blunt … there is going to be a much greater focus on security, as well as the need for the rights of non-Arctic states to be observed,” Marc Lanteigne, a professor of political science at the University of Tromsø (UiT): The Arctic University of Norway, told CNA.

All these will only serve to further divide the Arctic, making it more challenging for other polar players to operate there, warn observers, adding that tensions will also spill over into the wider world as countries come under increasing heat to take sides.

GUNNING FOR GREENLAND

Greenland, an autonomous territory in North America administered by Denmark, was previously courted by Trump during his first presidential term from 2017 to 2021. Despite being roundly rebuffed, Trump’s desire to acquire the world’s largest island has endured as he embarks on a second stint in the White House.

“For purposes of National Security and Freedom throughout the World, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity,” then-President-elect Trump posted on Dec 22 last year on his Truth Social platform.

Trump doubled down in a press conference two weeks later, telling reporters he would not rule out using military force or economic coercion to take control of Greenland. While that was happening, his eldest son Donald Trump Jr was visiting the territory on a self-proclaimed private day trip.

Trump’s remarks, reflecting an expansionist agenda that was further observed in his inauguration speech, have become “much more direct” this time around, showing how Greenland “very much” occupies his strategic thinking, Lanteigne noted.

Regardless of whether the businessman-turned-president’s Greenland gambit pans out, analysts agree that the US will continue training its sights on the island due to its growing strategic import.

Its rich but largely untapped resources are a key factor. Twenty-five of the 34 minerals identified as “critical raw materials” have been found in Greenland, according to a 2023 European Commission survey.

“Rare earths are especially of interest, because right now China has a considerable presence in most of those industries, and Trump has made it clear he kind of wants to break China’s dominance in these areas,” Lanteigne explained.

Rare earths are critical components for an array of everyday tech products like smartphones, computers, televisions and magnets. China dominates the field, controlling about 55 per cent of global mining capacity and about 85 per cent of refining, according to an Oct 2024 commentary by the Brookings Institution, a US think tank.

The US places a distant second. The world’s No 1 economy accounted for about 12 per cent share of global rare earths production in 2023.

At the same time, analysts say Trump is sending a clear message of deterrence as Russia and China expand their Arctic footprint. Cooperation between Moscow and Beijing in the polar north spans trade, science and the military, under their wider “no-limits” partnership.

“(Trump) is trying to send a very loud signal to Russia and China – that the US wishes to create almost a kind of protective cordon, or a buffer zone, around US Arctic interests,” said Lanteigne.

Russian militarisation of its Arctic territory and a greater Chinese presence in the polar north is a big factor animating the US’ current strategy in the region, Trym Eiterjord, a research associate at the Washington DC-based think tank The Arctic Institute, told CNA.

“Controlling Greenland would presumably serve to fence off that part of the Arctic from any further Chinese (or Russian) activities, which was a major concern during the previous Trump administration,” he said.

PURSUING THE PANAMA CANAL

Beyond Greenland, US President Donald Trump has also set his sights on acquiring the Panama Canal on the grounds of national security. He has similarly refused to rule out economic or military coercion to this end.

The 80km international waterway effectively provides a shipping shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, allowing vessels to avoid the lengthy, dangerous voyage around the southern tip of South America.

Trump has accused Panama of charging excessive rates to use the Central American passage while also alleging, without basis, that China is involved in its management and that Chinese soldiers operate the canal.

“It’s being operated by China. China! We gave the Panama Canal to Panama, we didn’t give it to China,” Trump said in a freewheeling press conference at his Mar-a-Lago resort on Jan 7.

Trump doubled down on his assertions in his presidential inauguration speech on Jan 20. “China is operating the Panama Canal, and we didn’t give it to China, we gave it to Panama, and we’re taking it back,” he said.

China does not control or administer the Panama Canal, although a subsidiary of Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings has long managed two ports on both ends of the waterway.

Panama leaders have pushed back strongly on Trump’s threat to retake the key global waterway, which the US had built and owned before handing over control in 1999.

China has also weighed in. “China will as always respect Panama’s sovereignty over the canal and recognise the canal as a permanently neutral international waterway,” said a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson in late December.

Trump’s remarks have stirred controversy and hinted at the aggressive foreign policy he is expected to take during his second presidency.

Analysts say the chances of the Trump 2.0 administration taking the Panama Canal by force are unlikely.

The US position in Latin America would be severely undermined if Trump were to proceed, cautioned Amalendu Misra, a professor of international politics at Lancaster University.

It would prompt many nations in the region to pull out from the Organisation of American States, which comprises more than 30 countries in the Americas, cautioned Misra in an article published by independent news site The Conversation on Jan 9.

“Worse still, it could also encourage many of the fearful nations to openly seek military alliances with enemies of the US, such as Russia, China and Iran – an outcome that would far from strengthen US security,” he said.

Either way, Trump’s expansionist rhetoric has already wrought harm to America’s reputation, said Gideon Rachman, chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times.

“Even if Trump never makes good on his threats, he has already done enormous damage to America’s global standing and to its alliance system,” Rachman said in a Jan 15 commentary on CNA.

“Any sniggering at Trump’s ‘jokes’ is misplaced. What we are witnessing is a tragedy – not a comedy.”

Collapse Expand

RECALIBRATING CHINA’S ARCTIC STRATEGY

Greenland has baulked at becoming part of the US, even as the autonomous territory – located in North America and part of Denmark for 600 years – forges a path to eventual independence.

“We want to be Greenlanders,” said Greenland’s Prime Minister Mute Egede in a Fox News interview on Jan 16. “But we want to also be clear: We don’t want to be Americans. We don’t want to be a part of (the) US, but we want strong cooperation together with (the) US,” he emphasised.

Whether Trump obtains Greenland or not, observers point out that his actions will likely prompt Beijing to align itself further with Moscow in the Arctic, in order to preserve its strategic interests in the High North.

“The biggest interest for China (in the Arctic) is resources and energy security,” Liu from SMU told CNA.

China has invested over US$90 billion in the Arctic region over the past decade, largely in infrastructure projects centred on the energy and minerals sectors, according to the US House Foreign Affairs Committee.

Much of these have flowed to projects in the Russian Arctic, such as the Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG 2 plants, as well as the Power of Siberia pipeline that transports natural gas from Russia to China.

“For a major economy like China, they need to make sure – pretty much like the US – that they have priority for their resource demand and to fuel their economy globally,” said Liu.

Shipping is also a core interest for China in the Arctic, a point made clear in Beijing’s Arctic white paper published in 2018. The document described an envisioned “Polar Silk Road” through developing the Arctic shipping routes, while also controversially framing China as a “near-Arctic” state.

The Arctic is one of the biggest victims of climate change. Warming temperatures have opened up new shipping routes in what was once considered an impassable region, potentially shaving weeks off voyages between Asia and Europe compared to the traditional journey via the Suez Canal.

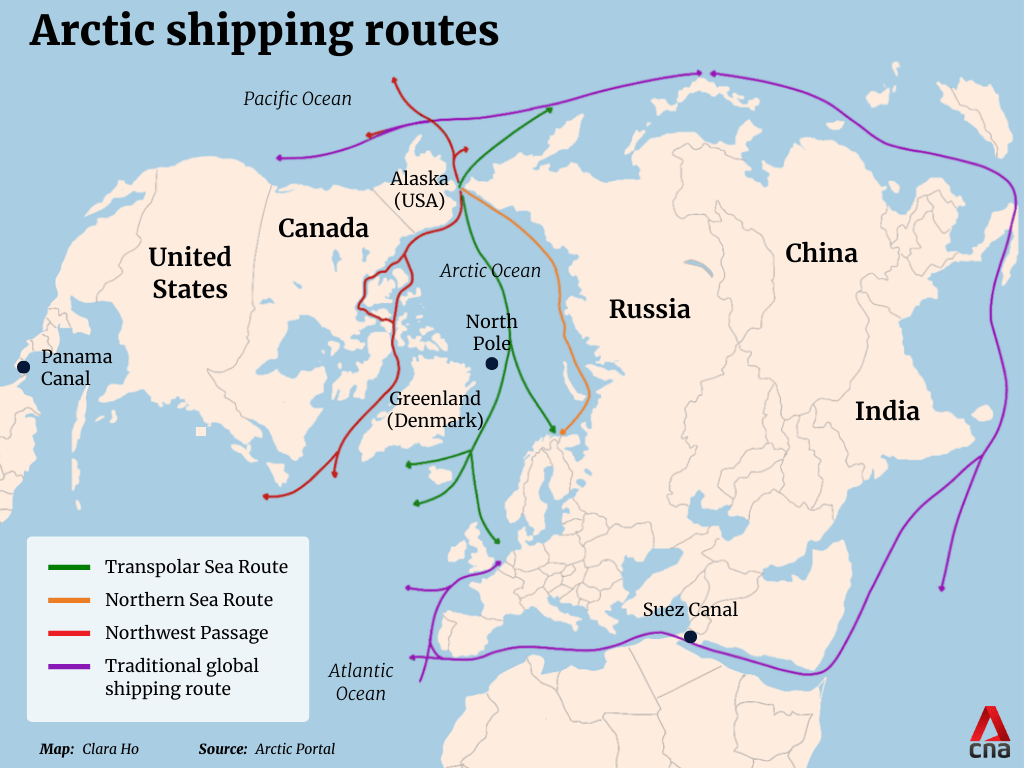

There are three main routes. The Northern Sea Route is currently the most-used due to its relatively favourable conditions, with most of it stretching along the Russian Arctic seaboard. Moscow and Beijing are partners in developing the sea lane.

Similarly, the Northwest Passage through the islands of northern Canada connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic.

But it’s the Transpolar Sea Route that is arguably the most closely watched. Cutting through the central Arctic, it is beyond the exclusive economic zones of all Arctic coastal states, boosting its attractiveness as a future trade route once the ice melts.

With research suggesting the Arctic could be ice-free in summer by the 2030s, the region’s strategic potential for trade and beyond has drawn international attention, including from China.

“China is trying to prepare for a time where it can expand its commerce there (the central Arctic). But for now, it’s still very much at the mercy of the Arctic states, including Russia,” noted Lanteigne from UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Other countries at varying distances to the polar north have also stepped up involvement in Arctic affairs. Climate-vulnerable nations like Singapore are particularly concerned about the existential consequences of the melting polar ice, while shipping and science take precedence for others.

While Russia has historically been cautious about inviting any foreign power into its Arctic backyard, this stance has softened towards China at least as Moscow becomes more economically and politically dependent on Beijing amid tough Western sanctions, imposed following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

On its part, China is now much more dependent on Russia for access to the polar region as Sino-US tensions flare and the Arctic states view Beijing with growing mistrust, stalling cooperation, experts noted.

Lanteigne noted that China initially tried to court other Arctic states, directing investments at Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland, to name some.

“Very few of these projects have actually come to fruition. There was all kinds of talk about Chinese mining in Greenland. None of that has come about,” Lanteigne pointed out.

China has faced “a lot of pushback” from the US and other NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) governments, noted Eiterjord from The Arctic Institute.

HIGH NORTH, HIGH TENSION

Warming ties between China and Russia in the Arctic will raise the geopolitical temperature in the polar region by further dividing it into two camps – the two countries in one, and the US and allies in another, observers warn.

“Geopolitically, the Arctic is sadly becoming a confrontational zone again … which is very, very sad for the Arctic, a place on the planet that is heavily affected by climate change,” said SMU’s Liu.

Liu brought up how the Arctic became a heavily militarised region during the Cold War. “Basically, the US and Soviet Union had missiles targeted at each other,” he remarked.

While the reality is far from that in the present day, analysts say what’s clear is that the Arctic is becoming more militarised once again as competition trumps cooperation.

Between 2014 and 2019, Russia built more than 475 military facilities in the Arctic, according to an April 2024 article by US news site Foreign Policy.

There has also been combined China-Russia military activity in the Arctic. In July 2024, nuclear-capable strategic bombers from the two countries flew over the Chukchi and Bering seas. It was the first time Chinese bombers flew within Alaska’s air defence identification zone.

China and Russia also held joint naval exercises in the Bering Strait in 2023. And in October 2024, China’s coast guard claimed it entered the waters of the Arctic Ocean for the first time as part of a joint patrol with Russia.

On the Western front, Trump is gunning for Greenland without ruling out economic or military coercion. “I’m talking about protecting the free world,” Trump said in a news conference earlier this month.

Meanwhile, NATO is bolstering its Arctic presence in response to Russia’s growing shadow. All of the Arctic states barring Russia are members of the alliance. The newest entrants, Finland and Sweden, were galvanised to go from neutral to NATO after Russia’s full-blown invasion of Ukraine nearly three years ago.

“I think that if we really start to see NATO become much more active in the Arctic as well as increased US strategic presence in Greenland, first of all, Russia will respond, it will continue to try and build its own Arctic military capability,” said Lanteigne from UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

“And I think that China will have to redirect its efforts because China has made it very clear that the polar regions are a strategic new frontier.”

Lanteigne noted that China, through its press, has been trying to paint the US and NATO as responsible for militarising the Arctic.

“These criticisms, they tend to ignore Russia, they say: ‘Well, the Arctic was a very strong area of cooperation, scientific accord, and NATO came along and ruined it.’”

Analysts agree that security will be the primary focus of China’s evolving Arctic policy.

China’s 2018 white paper had “very limited discussion” on security and tried to avoid giving any impression that China was “trying to be a spoiler” in the Arctic, said Lanteigne.

“But that was done with China hoping that it would not be seen as an aggressor, as someone who is trying to counter-balance the Arctic powers,” he said.

“This is no longer an issue. China is no longer able to really put forth the idea that it is a neutral partner, trying to be a helper.”