When the Trinidad, Victoria and Concepcion anchored off Leyte island in 1521, the destiny of the Malay/Austronesian peoples inhabiting a chain of more than 7,000 islands was to be forever changed. The Spanish had arrived in what would come to be known as the Philippines.

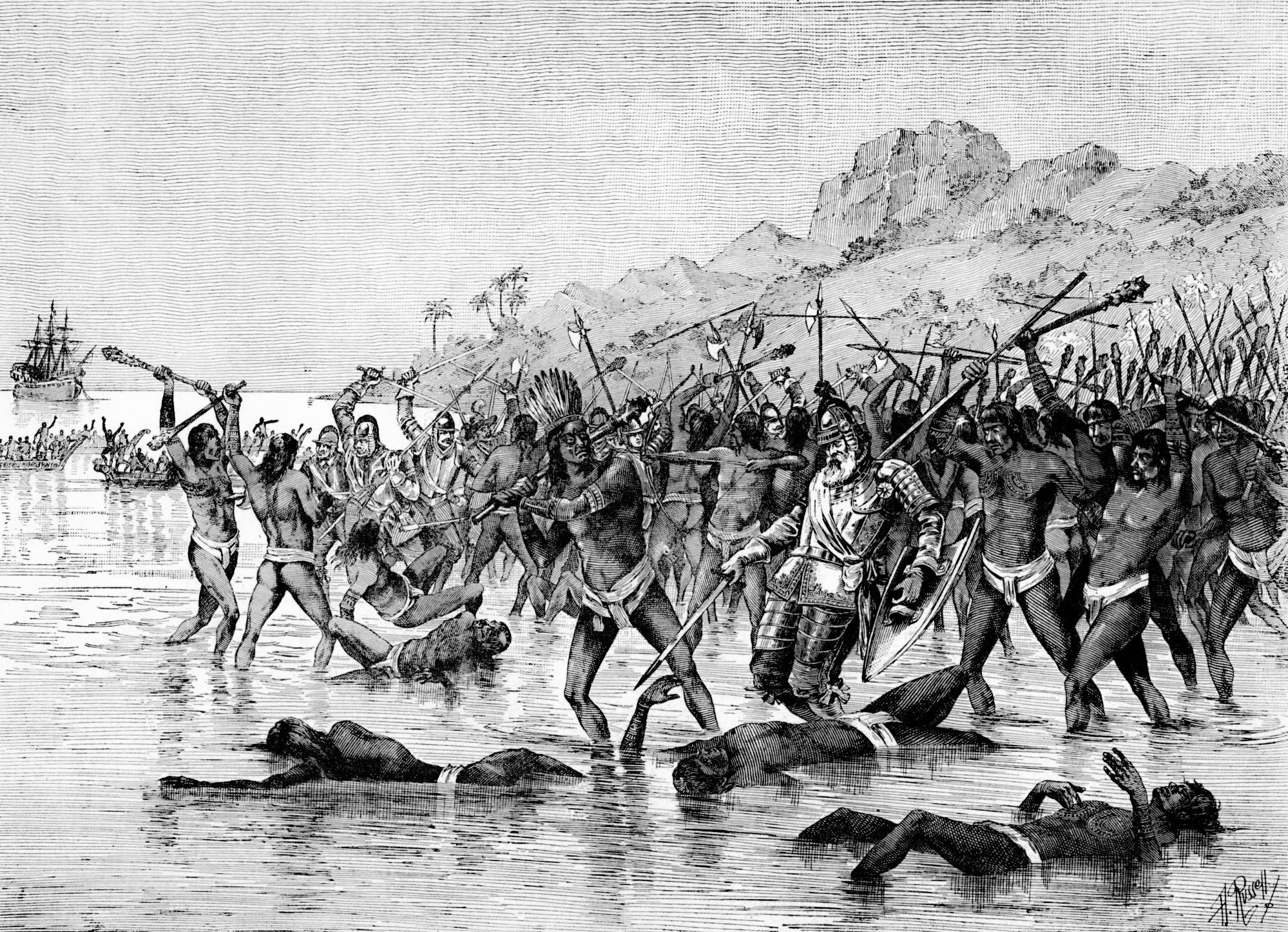

Things did not get off to a good start. The expedition leader, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, found willing converts to Christianity on Cebu, but Lapu-Lapu, rajah of neighbouring Mactan, did not take kindly to cavalier Iberians intruding on his sun-kissed realm.

Magellan and a number of his men were killed in battle. Those who survived sailed on, a few of them managing to complete the first known circumnavigation of the globe.

As news of the discovery of these resource-rich islands spread, the Spanish were resolved to return. Over subsequent decades, the archipelago was merged as one polity and named Islas Filipinas, after Spanish king Felipe II (1527-1598).

Subsequent colonisation by the United States, devastation during World War II and developments in the decades that followed independence, in 1946, have done much to mould the contemporary character of the nation.

Yet three centuries of Spanish rule left an indelible mark on the Philippines, evident in place names, tasted in distinctly Hispanic cuisine and audible in the Latin words that have found their way into the Filipino lexicon.

Much material culture left by the Spanish has been lost to the tropical climate and natural disasters. But to glimpse what survives, it’s best to begin where the colonial project dropped anchor.

Cebu International Airport is on Mactan, the island where Magellan was slain. Next to the airport is a cluster of luxury hotels and dive resorts named Lapu-Lapu City, after the battle’s victor.

A short jeepney ride across one of the two bridges that span the Mactan Channel takes arrivals into Cebu City proper, a ramshackle metropolis splashed across the southeast side of Cebu island like a concrete tidal wave, rivers of anarchic traffic bisecting neighbourhoods of new high-rise residences and bric-a-brac low-rise slums. Yet this is, arguably, the nation’s oldest city, known to maritime traders of antiquity as Sugbo.

Ships from the Spice Islands, in present-day Indonesia, Siam (as Thailand was then called) and China had berthed in Cebu’s turquoise waters for centuries. And so it was here that Miguel Lopéz de Legazpi arrived from New Spain (present-day Mexico) in 1565, to begin the Spanish conquest of the Philippine islands.

Parian district is home to Cebu City’s principal heritage sites, the most imposing of which is the Fuerza de San Pedro, a triangular, sea-facing stone fort built just after the Spanish arrived, although significantly reinforced during the 17th century.

It has since served as an American military base, a Japanese prison camp, even a private club. It is now a museum, a tour of which begins with exhibits related to the arrival of Magellan and his first encounter with the Cebuanos.

Lapu-Lapu is regarded as a patriotic hero and the Philippines birthed the first anti-colonial movement in Asia, so the local reverence for Magellan can be difficult to process.

But a few blocks inland, it’s clear that what is being observed is not the arrival of the Spanish per se but of Christianity, the focus of which is Magellan’s Cross, which is made of black tindalo wood and housed in a pavilion in the middle of Plaza Sugbo.

Although it’s unclear whether the original cross survives or Legazpi replaced it, devotees come in their droves to pray before the wooden relic.

Nearby is the Santo Niño Basilica, the oldest Catholic church in the Philippines, founded in 1565. Following fire and earthquakes, the church seen today was built in 1735, although it, too, has been restored numerous times.

Still, the basilica remains an enigmatic structure, whitewashed and water-stained, “a centre of intense devotion and religious pilgrimage throughout the Visayas [a group of islands in the central Philippines, including Cebu]”, according to the Philippines Historic Committee plaque attached to an exterior wall; it is also an architectural icon worthy of a city that calls itself Queen of the South.

The Spanish did not just bring religion to the Visayas, as Museo Sugbo – housed inside an old prison – explains. Political detractors withered away in obscurity in the prison along with criminals.

Notwithstanding its gloomy legacy, it is an attractive old casa – a distinctly 19th century Spanish building centred on a fountain and paved stone courtyard.

Former prison cells house galleries that provide a more secular reading of Cebu’s story, from the pre-colonial period through the Spanish and American eras, to the islanders’ experience under imperial Japan and afterwards.

Legazpi left Cebu in 1571 for “Maynila”, another time-honoured trading port, where he set to work building a capital for the Spanish East Indies, which included Guam and other Pacific territories.

Although troubled by foreign invasion (including occupation by the British between 1762 and 1764) and periodic episodes of unrest, Manila flourished as a key node in the trans-Pacific galleon trade: ships sailed back and forth to Acapulco in Mexico weighed heavy with porcelain and pearls, silk and silver.

There is little to evoke the past in Metro Manila. The capital region was all but erased from the map in the final months of World War II. The result is a concrete jungle that has grown out of the ashes of war, a product of 20th century urbanism, ill-planned and congested.

If you head west from the Manila Hotel, however, and beyond Rizal Park, you’ll eventually come to the walled enclave known as Intramuros. Although not quite the bustling city of yore – it is now encircled by an American-built golf course that covers the old moat – this is what’s left of Spanish Manila.

Intramuros is a bold expression of urban renewal, having been rebuilt from the jumble of broken buildings to which it was reduced during the Battle of Manila in 1945.

Nowadays, visitors can wander between fully restored Spanish buildings, hopping from cafe to handicraft store to boutique hotel.

The imposingly Romanesque Manila Cathedral is Intramuros’ centrepiece. Like the Basilica in Cebu, it has been rebuilt so many times since 1571 that it is said to represent “the resilience of the Philippine people”.

Sunday sermons here are so popular, the congregation floods the Plaza de Roma outside the cathedral, singing hymns in both the national language Tagalog and English.

A five-minute walk northwest of the plaza leads to the gates of Fort Santiago, a partially rebuilt Spanish citadel that also dates back to Legazpi’s time.

It’s a wellspring of history, including that of Dr José Rizal (1861-96), the author and agitator who is credited with fomenting the overthrow of Spanish rule.

Rizal’s eponymous museum, as well as the cell where he is said to have spent his last night, writing a poem to his people, are both here.

At the head of the fort are the subterranean chambers in which the Japanese jailed allied soldiers – often until they starved to death – during World War II.

A stroll along the citadel walls beside the Pasig River is rewarded with views of Binondo, the old Chinatown, neon-hued and bustling, just across the rippling maroon water.

For a more surreal taste of the Spanish Philippines, you’ll have to commit to a seven-hour night bus journey from Manila up to Ilocos Sur, a province on the northwest coast of Luzon.

The reward is to arrive in Hispania circa 1700, with horse-drawn kalesas trotting along cobbled streets lined by architecture that mixes Mexican, Chinese and Filipino features.

Vigan is a Spanish colonial town that boasts 233 historical structures, some of which have been converted into hotels, so finding a bed is easy. It’s also small enough to explore on foot.

The most attractive casas can be found alongside the streets that run from Liberation Boulevard, in the south, to Plaza Burgos, in the north, and although some are crumbling in the humid equatorial climate, many house places to eat or handicraft stores that sell everything from Jesus effigies to Ilocano textiles. It’s easy to spend a day just wandering.

West of Plaza Burgos, past the mustard-coloured city hall, stands Padre Burgos House, a beautiful, whitewashed, concrete-and-wood structure surrounded by landscaped gardens that was home to Padre José Burgos, whose martyrdom in 1872 galvanised the revolutionary movement.

From 1972 to 1975, the building served as a bank, and the teller windows on the ground floor can still be seen. Today it and the adjacent former county jail serve as a museum dedicated to Burgos’ legacy and Ilocano cultural traditions.

Across the Govantes River is the imposing, if partially ruined, Bantay Watchtower, which was built in 1591 to help the Spanish oversee their newly built town. The word bantay means “guard” in Tagalog.

It was later converted into a bell tower for the neighbouring church, which was built in 1857.

The fading beauty of Unesco heritage-listed Vigan is enhanced by the orange hue of the dipping sun. Bats appear, swooping overhead, children scoot past on rusty bicycles and the air smells of fried pork belly and freshly baked pastries.

Instinct, and a good thirst, leads me to Calle Brewery, a craft brewery selling Philippines-themed beers.

Sipping an Espada ni Lapu-Lapu, a wheat ale, while sitting on the outdoor terrace, a visitor could be forgiven for imagining the night bus had actually transported them across the sea to some distant corner of Sudamerica.